MOMENTUM’s exhibition A WAKE travels to New York!

A WAKE at the Dumbo Arts Center

1 – 25 November 2012

Due to hurricane, delayed until 9 Nov

Dumbo Arts Center (DAC)

111 Front Street, Suite 212

Brooklyn, NY 11201

WORKS BY:

Osvaldo Budet

Annika Eriksson

Yishay Garbasz + Nikola Lutz

Anna Bella Geiger

Stephan Halter

Jarik Jongman

Betty Leirner

CURATED BY: Rachel Rits-Volloch, Adam Nankervis and Leo Kuelbs

ABOUT THIS EXHIBITION:

A WAKE is consciousness with an eye on an open coffin. A gathering in celebration as well as mourning, it is humor as much as horror. As a platform dedicated to interrogating time-based art, with A WAKE, MOMENTUM explores what happens when our time runs out.

MOMENTUM celebrates the Day of the Dead, Los Dios de los Muertes, with A WAKE: Still Lives and Moving Images. This exhibition combines, video, cinema, and photography in a co-mingling of media which bring the still into motion, and the motion into emotion. The exhibition takes the form of a processional of monitors leading into the gallery itself, which will be oversaturated with projections. In the tradition of inviting the dead to a party with the living, we crowd the gallery with the conversations of flickering ghosts; a saturation of images in dialogue with one another. Reflecting upon our daily inundation by images of death, where news programs sensationalize death no less than the fictions of TV shows and feature films, A WAKE addresses the media as the Vale of Tears, the surface between now and the hereafter, as well as the past. Co-mingling archival films with contemporary art, we enact a conversation across mediums and generations to celebrate life as well as death.

A WAKE is a ritual viewing of the body after death; a coming together to observe the end of time, to celebrate the transition through the vale. It is also an emergence into consciousness, as well as a consequence or result. Taking this transitional point between being and representation as our title, A WAKE confronts us with the process and the presence of

death in order to wake us up to the inevitable result of the passage of time. The works in this show all use video, digital media, and film to address the mediation of death; where media itself becomes the vale/veil through which we pass, the translucent surface between observer and observed, between now and the hereafter. All the works in this show manipulate media forms in some way, whether in mobilizing still images into motion, or in bringing together past and present, fiction and reality, re-editing found footage, re-visiting rituals, or re-living the horrors of war.

All cultures acknowledge the Day of the Dead. Some celebrate, others mourn, but the ineluctable culmination of life is a part of every belief system, and of every personal journey. Opening the weekend of All Saints Day, Los Dios des Muertes (The Day of the Dead), A WAKE is held in the once upon a time infirmary within the former cloisters of Bethanien House Berlin. Originally built as a hospital, a space both battling and housing death, Bethanien has long been transformed into a place where art through the process of creation manifests the victory of life over death. We fill this space with a labyrinth of screens which illuminate still lives and moving images. A WAKE is a passage through time, a processional which is our “offerenda”, an offering to visiting souls awakened on this day every year. Through the translucent veil of time-based art, past, present and future meld into one in this metaphysical meditation on the passing of being into representation.

FEATURED WORKS:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

`

“Défilé” (2000-2007), dig projection, 7 dig photos. “Who Wants To Live Forever” (1998), 6:25min. In «Défilé» we explore the way individuals deal with the concept of mortality by juxtaposing images of death with images of beauty, in this case high fashion. In pairing fashion with death, we have found a modern-day counterpart to the traditional juxtapositions of love and death and beauty and death. An obsession with fashion, symbolizing temporality, can be seen as a way to deal with the fear of death. It is an ancient preoccupation, as can be seen in the elaborate rituals in Western and non-Western cultures associated with death. Humans have always attempted to «decorate» death, based in part with a desire to ward off death. “Who Wants To Live Forever” is a critique of the global media, addressing not only the media, which uses the sexual scandals and the death of the celebrities but also the exhibitionistic behavior of the media star. The career top of a media star, who produces nothing but his face on the screen, is death.

|

|

|

|

`

“Creative Wakes” (2011), dig video, 10 mins. Puerto Rico – In the fall of 2008, Angel Luis Pantojas told his family that in the case of his death, he wanted to be presented at his wake in a standing position. Two weeks later, he was fatally shot. His family fulfilled his death wish, and this triggered the beginning of a movement of themed and theatrical wakes in Puerto Rico. Osvaldo Budet explores the possibilities that this new trend has awoken. With his documentary-based practice, Osvaldo Budet consistently blurs the line between reality and representation.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

`

“The Great Good Place” (2010), dig video. This video shows the life of a community of abandoned indoor cats living in a park in Istanbul. “The Great Good Place” was shot in Istanbul, documenting the street cats who live in dwindling numbers throughout city. A regular urban presence, when removed from their environment they appear eerie, floating in darkness. In the context of this exhibition, they seem like creatures of the night; familiar sights on the streets of Istanbul, becoming familiars of a more supernatural kind. But perhaps they remain, after all, simply cats upon which we project our own realities. During 2012 ‘’The Great Good Place’’ has been shown in the first international Kiev Biennale as well as the Shanghai Biennale.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

`

“N 37° 25′ 20″, E 141° 1′ 58″” (2011), dig video. This piece comes out of the reactions of the artists to the Fukushima nuclear disaster and devastation. The piece invokes elements of life and death via the sounds and visuals of surgery as well as fire and the human body. The risk involved in the actions depicted helps set the scene. There were no special effects used in doing the fire performance. This is the first collaboration between Yishay Garbasz, a photographer working with the body and the mobilization of images, and Nikola Lutz, a musician and sound artist. The piece is dedicated in gratitude to the memory of Dr. Johannes D. Lutz, who passed during the making of this work.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

`

“Passagens n.1″ film converted to digital media, 1974

Passagens n.1, is a video from the series I titled Situações-limite. The point of the piece is to bring visually, through repetitive movements of my climbing stairs – a sense of unfinishable path. Changes of scenery, going through narrow and broad steps, inside – outside, bringing a sense of continuity/ discontinuity, the difficulty of crossing. In my three repetitions (inside and outside stairs scenes) I perform slight differences, and the tiresome effort increases. In this and other videos from the same period I deal with the symbolic and also with the specific language of video. For instance, the movement of the artist crossing the cathodic tube in its 4 corners, creates an invisible center of the image.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

`

“Schlaflied” dig. 720p HD-Video, 3:54min. (Berlin, 2011). Premier. Schlaflied is a German lullaby sung to children at bed time. Projecting a diapositive on the backyard walls of Wedding, the most war ravaged area of Berlin in World War II, the slide shows a cemetery of soldiers in France. Halter, through this performative action explores a futility. A futility in the loss of life. The futilities of war.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

`

“Sachsenhausen” (2009/2010) dig projection, 14 photographs. Premier. Predominantly a painter, the starting point for my paintings is always photography and it is now for the first time that I’m showing a series of photographs that were taken at the concentration camp Sachsenhausen, during a three month residency period in Berlin, in the winter of 2009/2010. Taken with a Lomo camera and presented digitally, the result merges the painterly, the photographic, and the cinematic. Thus blurring of media creates a timelessness most jarring in this tragic location situated shockingly close to Berlin.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

`

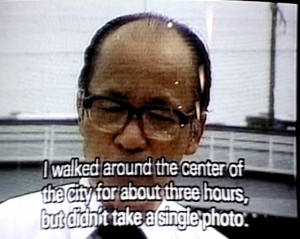

“The Testimony of Hiroshima a Fotofilm” (1999) 1:54min.

Among other atomic bomb survivors, Matsushige Yoshito continuously tells his story at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. In 1945, at the time of the dropping of the atomic bomb, the 32 year old journalist was at home at a distance of 2.7 kilometers from the bomb hypocenter. ‘The Testimony of Hiroshima’ is an hommage an Matsushige-san, who passed away in 1995. The film describes the three hour lapse of time in his life when he was unable to photograph death and pain.

|

|

|

|

`

“The Ghost of Isaac Newton in Another Vacant Space” (2011), video performance. David Medalla presents a video impromptu. Eienstein is walking on the road of Biesentalerstrasse Berlin when he sees the ghost of Isaac Newton, eating an apple, addressing an empty room in another vacant space. A dialogue ensues…. David Medalla is constantly shifting his strategies and media; when one thinks one has him pinned down as a situationist, a surrealist, or a conceptualist, one is stumped as he continues to endlessly conceive other fantastic, often unrealisable schemes. He is an icon of an artist who has made no clear distinction between his art and his life in a body of work stretching back to the sixties.

|

|

|

|

|

`

“Doomed” (2007) video, (Tracey Moffatt collaboration with Gary Hillberg), 10mins. This fast-paced montage of film clips takes Hollywood’s fixation with death and disaster to its ultimate cinematic end. “Doomed” comprises cut-and paste editing techniques in a highly entertaining and blackly-humorous take on the bleak side of our current psychological landscape. Moffatt’s film looks at both entirely fictional and reconstructed disastrous events. Each scene carries a particular cargo of references. They occupy their own unique symbolism and filmic territory – the poignant, sublime and epic, the tragic, the B-grade and downright trashy. The accumulation of scenes creates a narrative whole comprised of parts. Moffatt plays with the ‘disaster’ genre, re-presenting representations. Looking at the forms of filmic entertainment, as well as ‘art as entertainment’, she addresses what it is about death and destruction that we invariably find so entertaining. Music manipulates. The soundtrack builds and peaks – emotive, and a central device in journeying through the sequence to climactic effect. It is important that the title ‘Doomed’ has the quality of the not yet destroyed. It is a description that is applied to individuals, families, lovers, politics, and nations – an observation made from the outside and yet containing the possibility (read hope) that situations can be salvaged.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

`

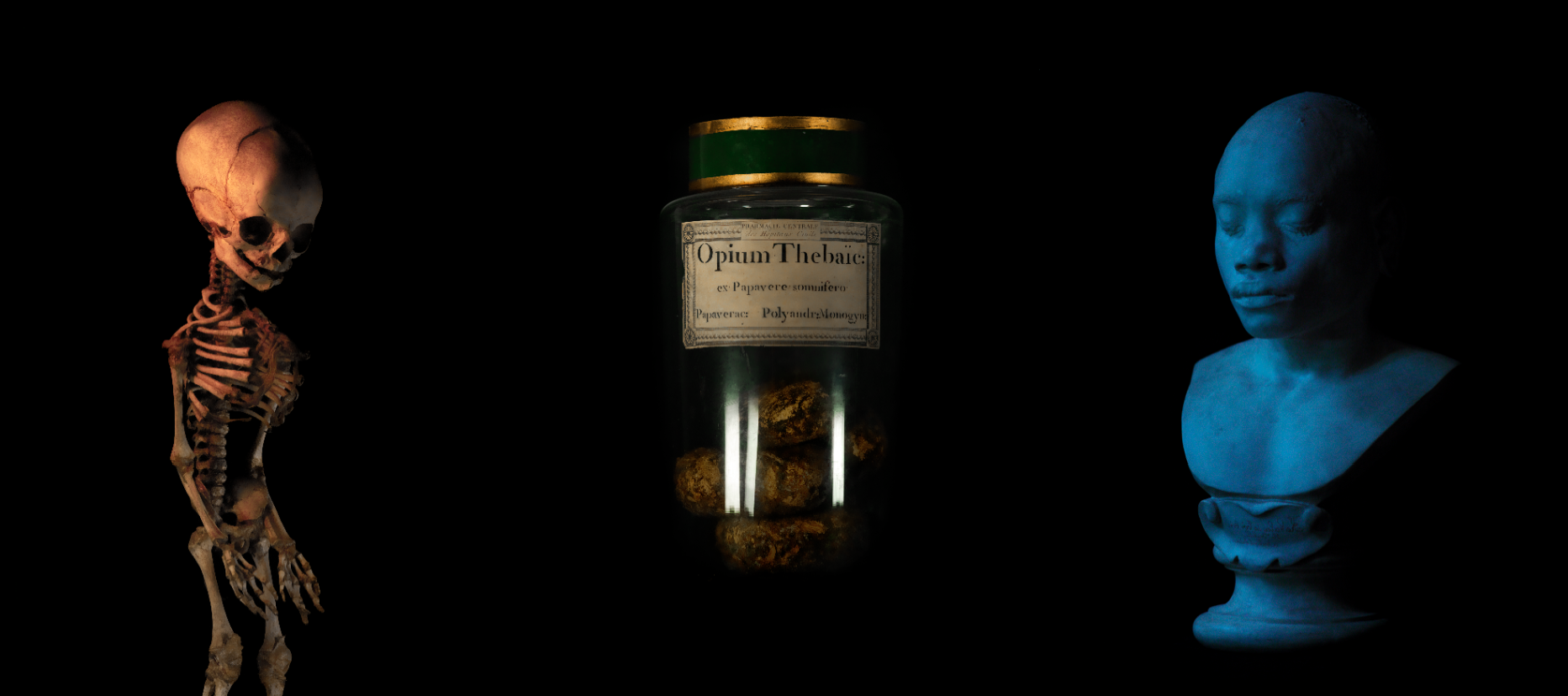

“We Dream of Gentle Morphius” (2011), from “Organic” dig projection of the photo series “Still Lives”

Fiona has been working in a still-life format within museums, recording taonga (Māori ancestral treasures) and other historic objects such as hei tiki (greenstone pendants) and the now extinct huia bird. In these works, she brings to a contemporary audience an awareness of traditional and forgotten objects. Her art practice occupies itself with both memory and mourning, and the ineffability of the photographic image. Her photographs demonstrate a mastery of analogue darkroom technique combined with the digital. Presented for the first time as a digital projection, these combined images, says Fiona Pardington, “work on a number of levels – once again my whakapapa/genealogy – random items that belong to beloved family members and important family members i had little contact with – like a child’s silver christening cup found by chance in a skip by my aunt when my grandmother’s house was cleared after sale- it belonged to my father…silk scarves found in french flea markets, shells taken from beaches important to ngai tahu because they are mahinga kai/traditional food gathered from the sea….seaweed, bottles dug out of the sand, midden shells from the beach the ngai tahu cheif tangatahara lived near. paua shells from otakou- paua shells are important food but also the shell can be seen as a tourist cliche and is sitting in a strange NZ cultural limbo presently. crystal wine glasses from op shops, native flowers and introduced weeds and pest plants introduced from overseas by the colonizers….”

|

|

|

|

|

`

“Loom” (2010) dig animation, 5:30mins.

Loom tells the story of a successful catch. A moth being caught in a spiders web. Struggling for an escape, the moth’s panic movements only result in less chance of survival. What follows is the type of causality everyone is expecting. The spider appears, claims its prey and feeds on it. The way nature works. But it’s the point of view that creates an intense relationship between the hunter and its victim. There is much more to explore, much more to feel if one takes the time to really experience the content of a split second. Polynoid uses digital animation to heighten the senses, turning the natural into the hyper-real with a virtuosity of technique blurring the line between the digital and the science of life and death.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

`

“Crash” (2009) Series, 3 Videos #1

“Crash” is a car accident scene that continously reveals one picture forward and at the same time continues to repeat itself. Gradual picture exposing strengthens the curiosity of what would happen next, multiplication intensifies the brutal tension, which can emanate with outrageous beauty. Finally, tension and tempo can bring on a visual catharsis. In drawing out a moment of film to manipulate the media and the viewer, Paul Rascheja confronts the basis of our fascination with violence. Too horrified to look, yet too mesmerized to look away, we are caught in this endless moment at the cusp of life and death.

|

|

|

|

|

`

“Night and Fog” (Nuit et brouillard) 1955, 32 minutes

Knowledge and memory change with time – this is one of Resnais’ thematic concerns, in this film and elsewhere. “Nuit et brouillard” is a remarkable documentary made 10 years after the end of WWII, constructed and reconstructed out of a blending of archival footage and then-contempoary sequences. The contemporary (colour) sequences were shot at Auschwitz and Maïdanek, authorised and financially supported by the Polish government. The past, in black and white, was reconstructed from documentary material and stills gathered from concentration camp museums. It is precisely Resnais’ obsession with and mastery of form that gives Nuit et brouillard an emotional power unequalled by any fictional reconstruction of the Holocaust. The near-digressions of the subtly orchestrated and edited filmic narration and the ironies of the commentary capture and focus the viewer’s attention, ensuring that the most horrible images (those shots of corpses, for example, that the censors objected to) are seen with clear eyes, and that therefore their human meaning cannot be avoided. The juxtaposition of past and present ensures that the final question (“Alors, qui est responsable?”/”Well, then, who is responsible?”) is directed at the viewer, any viewer, the viewer of 1956 (when, Resnais admits, the growing war in Algeria was much on his mind) and the viewer today, living in an era of ethnic cleansing, genocide, and state violence differing perhaps on target but not in effect from those that came before. West Germany became the first country to purchase and distribute “Nuit et brouillard” when it came out. In the context of this show, it is important to bring it back.

|

|

|

|

|

`

Known as a forefather of both Czeck surrealism and animation, it is ironic that this is perhaps Svankmajer’s only documentary, yet it could so readily be misconstrued as one of his elaborately constructed fictions. One of the masterpieces produced during Švankmajer’s early career, Kostnice (The Ossuary, 1970), is shot in one of his country’s most unique and bleakest monuments, the Sedlec Monastery Ossuary. The Sedlec Ossuary contains the bones of some 50 to 70 thousand people buried there since the Middle Ages. Over a period of a decade, they were fashioned by the Czech artist František Rint with his wife and two children into fascinating displays of shapes and objects, including skull pyramids, crosses, a monstrance and a chandelier containing every bone of the human body. Their work was completed in 1870, and these artifacts have been placed in the crypt of the Cistercian chapel as a memento mori for the contemplation of visitors. Well-known for his appreciation of the macabre, Švankmajer found in Sedlec a subject sufficiently grim not to have to add very much to it. The theme of ageing, ruin and death appears right from the beginning. yet we are saved from morbidity by the elaborate, contrast-rich editing, alternating static images and leisurely camera pans with bursts of rapid-montage, swish-pans and tilts reminiscent of the impressionist technique of the pioneer of early French film Abel Gance. At other times, a long shot of the chapel’s interior, a sculpture or a camera pan is intercut with close-ups of a skull or another poignant detail, producing an atmosphere of nervous tension. A subtle detail in the concluding images of the film links the macabre atmosphere of death with the oblivion of the living: adolescent initials scratched into the skulls and bones by anonymous visiting vandals. A silent commentary on the eternal forgetting of humans—or perhaps their effort to laugh at death?

Back to Homepage

Back to Homepage