There’s No Place Like Time:

A Novel You Walk Through

A restropective of video artist Alana Olsen

//

A multimodal installation by Andi and Lance Olsen

27 May – 25 June 2017

OPENING:

Saturday 27 May 2017 @ 7 – 10pm

ARTIST TALK:

Sunday 28 May @ 3 – 4pm

The Intermedial Moment: Andi & Lance Olsen in conversation with

Cécile Guédon, Lecturer in Intermediality at the Faculty of Comparative Literature, Harvard University

Watch here the video of the talk >>

@ MOMENTUM

Kunstquartier Bethanien

Mariannenplatz 2, Berlin

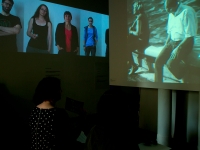

There’s No Place Like Time is a novel you walk through. It takes the form of a real retrospective of videos dedicated to the career of Alana Olsen, one of America’s most overlooked experimental video artists who never existed. An interplay of videos, texts, objects, and interventions, There’s No Place Like Time forms a multimodal installation that translates Alana’s life (which began as a fictional character in Lance’s novel, Theories of Forgetting [2014], based on Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty) into a three-dimensional reality. Andi and Lance Olsen’s collaboration explores the relationship between the visual and the verbal as it redefines the page, novel and gallery space. As well, There’s No Place Like Time thematically investigates the problematics of identity construction and historical knowledge.

CLICK FOR MORE INFO: www.zweifelundzweifel.org > >

Andi Olsen is an assemblage, computer-generated collage, and experimental video artist. Her videos have been exhibited in such venues as the American Visionary Art Museum (Baltimore) & Greenhouse Berlin (Germany), & have screened at the Los Angeles International Short Film Festival, Mütter Museum (Philadelphia), Revolving Museum (Lowell), & at literary and artistic events in Banff, Cologne, Munich, Paris, Rouen, Szeged, Warsaw, & across the United States. Her art has been exhibited & published around the country & abroad. Her ongoing solo project, Hideous Beauty, is a Cabinet of Wonders composed of short videos, assemblages, & collage texts exploring the idea of monstrosity & the generative possibilities inherent in the processes of decay.

Lance Olsen is author of more than 20 books of and about innovative writing. His short stories, essays, poems, and reviews have appeared in hundreds of journals, magazines, and anthologies. He is known for his experimental, lyrical, fragmentary, cross-genre narratives that question the limits of historical knowledge. In 2015-2016 he was a guest of the D.A.A.D. Berlin Artists Program. In 2013 he served as the Mary Ellen von der Heyden Berlin Prize in Fiction Fellow at the American Academy also in Berlin. A Guggenheim and N.E.A. fellowship recipient, winner of a Pushcart Prize, and governor-appointed Idaho Writer-in-Residence from 1996-1998, as well as a Fulbright Scholar, he is professor of innovative narrative theory and practice at the University of Utah.

ANDI & LANCE OLSEN – ARTIST STATEMENT

There’s No Place Like Time is a three-dimensional “novel” you can walk through. It takes the form of a real retrospective of videos, texts, objects and interventions dedicated to the career of Alana Olsen, one of America’s most overlooked experimental video artists who never existed, who also happens to be Lance’s protagonist from his novel, Theories of Forgetting (2014).

Alana’s experimental short videos (set in Berlin, Jordan, the U.S. Southwest, and elsewhere) span about 40 years: from her first forays into video-making as a child, through her investigations of the form in college, to her fully imagined works as an adult. During her later years, the videos reveal her attempt to explore various modes of innovation — employing a greater and greater use, for example, of text in her undertakings by way of erasures; the deployment of dubbed narratives at odds with the grammar of the visual pieces; and the investigation of words as another kind of image. Alana’s daughter, Aila, an art-critic and conceptual artist living in Berlin, curates the exhibition of her mother’s videos and provides a catalogue, biographical information and plaques describing her mother’s evolving aesthetics/obsessions and how each work fits into her development as an innovative video artist.

This collaborative project grows out of Lance’s novel, Theories of Forgetting, composed of three narratives. The first involves the story of Alana, a middle-aged video artist struggling to complete a short experimental documentary about Robert Smithson’s famous earthwork, The Spiral Jetty, located where the Great Salt Lake meets remote desert about a 100-mile drive northwest of Salt Lake City in Utah. The second involves the story of Alana’s husband, Hugh, owner of a rare-and-used bookstore in Salt Lake City, and his slow disappearance in Jordan’s Wadi Rum while on a trip there both to remember and to forget in the aftermath of Alana’s unexpected death. The third involves footnotes added to Hugh’s section by his daughter, Aila, an art critic and conceptual artist living in Berlin who discovers her father’s manuscript after his disappearance.

Theories of Forgetting and There’s No Place Like Time partake, then, in a larger project: a conversation with the conventional codex and the relatively recent flourishing of the book-art movement — namely, with works that consciously or unconsciously form a reaction against corporate mass reproduction and textual disembodiment in our digital age.

There’s No Place Like Time, the word “novel” is placed between quotation marks, then, because this project is not embodied in a traditional codex. Rather, it becomes a text one can walk through in a gallery space, and Alana’s character is developed through the videos, objects, plaques, novel and fictional catalogue.

The deep-structure thematics of both Theories of Forgetting and There’s No Place Like Time partake in Robert Smithson’s notion of “entropology,” a neologism the earthwork artist borrowed from Claude Lévi-Strauss that contains within itself both the words entropy and anthropology. Entropology, Lévi-Strauss writes in World on Wane, “should be the word for the discipline that devotes itself to the study of [the] process of disintegration in its most highly evolved forms.” For Smithson, entropology embodied “structures in a state of disintegration” — but not, provocatively, in a negative sense, not with a sense of sadness and loss. Rather, for Smithson entropology embodied the astonishing beauty inherent in the process of wearing down, wearing out, undoing, of continuous de-creative metamorphosis at the level, not only of geology and thermodynamics, but also of entire civilizations, and, ultimately, of the individuals living within them — like dying Alana, like forgetting and unforgetting Hugh, like Aila’s increasingly unfurling attempts to make sense of her father’s narrative, like me, like you.

In There’s No Place Like Time, we are interested at the level of character in Alana’s evolution as a human being as evinced through her art — through those short experimental videos she makes over the course of some four decades — and in how her daughter reads/constructs her mother through them, how that reading/construction reveals who Aila is behind the faux-authoritative voice she must by convention adopt in the catalogue and plaques she composes as curator of the exhibition of her mother’s videos. In other words, our supposition is that all writing, whether “critical,” “scientific,” or “creative,” is a form of spiritual autobiography. And to that extent we’re interested as well in how all biographies are, at the end of the day, not about the subject at hand so much as they are autobiographies about the problematics of historical knowledge and the fraught use of the third-person pronoun. We’re interested thematically in the realization such an exhibition invites of the entropologic processes at play within us all at a cellular level; how those processes are so present to us that they have become virtually impossible to see; how our cultures have taught us, by and large, to view them as a kind of subgenre of the horror film when in fact (as Smithson has it) they are simply (and perhaps even wonderfully) documentaries about who we are; in a very real way, after all, as Samuel Beckett maintained, “My mistakes are my life.”

Aesthetically, we’re interested, ultimately, in questions concerning intersemioticity — in the relationship, that is, between the visual and the verbal, in how one might begin to trouble such an easy binary. How does a specific medium (if we think not only of the codex or a website, but also, say, of the grammar of the gallery, as different sorts of media) affect the message it attempts to convey? Or, to put it another way, how do various technologies affect how various arts are expressed and experienced? How does one in 2016 write the contemporary — by our lights the essential task of any artist in any field at any point in history — and how does that writing (in the word’s most encompassing sense) help us re-imagine what a page is, what a novel, a gallery, what a narrative is as we navigate these concepts in a hypermedial format, or as we stroll through them in the shape of a three-dimensional novel? And how do such questions help us to think about what constitutes that always-already troubled and troubling term the experimental here, now?

ABOUT THE WORKS

Dreamlives of Debris

(Date unknown; 22:45.)

Dreamlives of Debris is a retelling of the minotaur myth. In Dreamlives of Debris however, the minotaur isn’t a monster with bull’s head and human’s body, but rather a deformed girl whose parents hide her away in the labyrinth below Knossos She calls herself Debris, and possesses the ability to hear, see, and feel the thoughts, memories, desires, pasts and futures of others throughout history.

This video/sound/text collaboration imagines the labyrinth, not just as a structure, but as a way of knowing, a way of being, an extended and dense metaphor for our current sense of presentness, of always being awash in massive, contradictory, networked, centerless data fields that may lead everywhere and nowhere at once.

Where the Smiling Ends

(1984; 7:20 min.)

Anthropology of loneliness capturing the moment, not when a photograph is taken, but just after, when one returns once again from the public to the private.

[ audio: Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings, op. 11 ]

Scarred

(1986; 17:33 min.)

The world continuously writes upon us, reminds us where we’ve been, that that place is real. Children treat their scars like badges of honor.

Lovers treat them like miraculous secrets. Old married couples treat them like familiar road signs. I don’t want to die without any scars, a character in Chuck Palahniuk’s novel Fight Club declares at one point. There is never any worry of that.

There’s no Place Like Time

(1988; 2:19 min.)

Avant-Pop appropriation & manipulation of one of the most famous

Merrie Melodies cartoons, Duck Amuck, & the existential moment:

the long-distance call, the stutter step, the instant where nothing happens—where Nothing happens—again & again.

[Audio manipulation: Judy Garland’s voice as Dorothy, from The Wizard of Oz]

Trace

(1991; 1:42 min.)

(excerpt from damaged film; original length 22 min.; no shot is longer

than 20 frames)

Olsen surreptitiously films performance artist Tehching Hsieh on the streets of New York during his non-performance performance during which he made art, but didn’t exhibit it. She reverses & complicates the

clichéd dynamics of the male gaze by becoming the female voyeur, Hsieh the subject made object, then complicates the complication by adopting the role of visual colonizer, Hsieh the Asian unwittingly colonized, thereby pointing to the fact that we are all complicit in the construction & enactment of unequal & multivalent networks of power. No one is ever innocent.

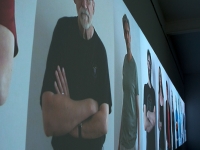

Self-portrait

(2000)

Enter & you find your vision crammed with people staring at you. Audio is 100% absent. Almost nothing changes while you stand there except

almost imperceptible shifts in postures, facial muscles. You are simply being noted: perceived, briefly marked down, acknowledged, studied, assessed, judged. You sense you areparticipating in one sort of event even as it sneaks up on you that you are actually participating in another.

Denkmal

(2006; 4:33 min.)

1213 photos of the Wannsee Conference Center outside Berlin, where the Final Solution was announced, transformed into a film accompanied

by an undoing of Adolf Eichmann’s testimony during his 1961 trial in Israel.

The aural manipulation consists of the phrases:

Zufriedenheit; das Ergebnis der Wannsee Conference; and zum Ergebnis der Wannsee Conference

[[ there. ]]

(2010; 5:40 min.)

Shot at various music concerts in Berlin, [[ there. ]]celebrates musicians giving themselves over to presence—a being there that paradoxically removes the musician from the seat, the room, the quotidian world in which he or she ostensibly resides. By being fully there, in other words, the player finds him or herself somewhere else.

Theories of Forgetting

(2016; 6 min.)

Olsen’s final film: a montage obsessed with Robert Smithson’s famous earthwork, Spiral Jetty, whose incongruous narration recounts the story

of a man standing in front of a video monitor in the Istanbul Modern, popping pills, until that narration is erased.

Family film and Alana’s 1st childhood film

Family footage (1:30 min.)

Alana’s childhood film (56 sec.)

One minute & thirty seconds of family footage my brother found among

my mother’s belongings. Here she is learning you can run across your

front yard with your eyes closed, playing a game with the neighborhood kids, for no reason at all. Here she is learning we don’t have to be anywhere.

Zweifel & Zweifel Galerie

www.zweifelundzweifel.org

Learn more about Alana Olsen at Zweifel & Zweifel Galerie, the first to host a retrospective of her work.

[design by Rotem of qiryat gat]

Photo Credit: Leslie Ranzoni

Photo Credit: Leslie Ranzoni

Back to Homepage

Back to Homepage