Yang Fudong: “The Revival of the Snake” and “Close to the Sea”

“Close the the Sea & The Revival of the Snake”, dual solo exhibition by Yang Fudong.

ShanghART Beijing & ARTMIA (261 Caochangdi, Old Airport Road, Chaoyang, Beijing). May 13–Jun 30, 2012.

Yang Fudong’s reputation is one cemented by years of popular practice in video art. A massive exhibition list precedes him, to which can now be added a dual solo show of 10-channel works at the adjacent ShanghART and Art Mia galleries in Beijing.

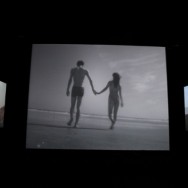

“Close to the Sea” (2004) follows a young couple on the beach. On one central screen (in monochrome), they are happy and carefree — strolling along the sand in swimsuits, burying each other, riding a white horse on the shore — but on the opposing screen they are adrift (in color): shipwrecked, clinging to a broken raft in bedraggled clothes. Other screens round the walls frame a familiar Fudong-cast of suit-clad men and women who play a discordant range of sounds on trumpets and other instruments, or at intervals simply stare into the middle distance. Next door at Art Mia, a dark room lined with rather lightweight excerpts from interviews with the artist precedes “The Revival of the Snake” (2005), wherein a soldier in exile struggles for survival in a hard Northern Chinese winter; in threadbare padded military clothes he wanders, sleeps, tries to smash the ice on a frozen lake and, at one point, follows a sparse funeral procession through the dormant, sun-grazed landscape. We see him bound and blindfolded as if sentenced to death by unseen interlocutors whom, we can surmise, lie within himself.

Such is the predominance of stylized technique in Yang Fudong’s work that its effect rests largely on one’s susceptibility to it. “Close to the Sea” is undoubtedly a skilled work, founded on tenets central to Yang’s practice: Chinese youth amid landscapes both outward and interior, acting on their own whims and simple pleasures, and at other times — simultaneously, for his videos refuse sequential narrative — abandoned and vacant in the same scenery turned sour. Our protagonists here, as elsewhere, appear fragile, easily thrown from their carefree plane as from a white horse onto a broken raft. The two looped threads create an unending rift of fate plagued by an a-melodic, Brechtian accompaniment that waxes and wanes not unlike the sea itself, and it is this inexorability coupled with the lack of pathos of the characters that can amount to a dubious pleasure to watch. It is in such unresolved, yet veneered existential events that the validity or rejection of the work lies — its intelligence, and its rub.

“The Revival of the Snake” entails a second existential atmosphere, benefiting from the substitution of lovers by a different brand of sentiment — that of war and its questionable heroisms: the romanticized defense of country, patriotism, loyalty, duty. These themes, however, have already been punctured in the moments portrayed. The soldier has (we assume) deserted the cause and is solitary, wanting of shelter and sustenance both spiritual and physical. Yang’s displacement of rational time is highly effective here, aptly illustrating the uncertain path the he has chosen to tread. The setting, too, is strong: the land he was fighting to defend is now his opponent — frigid, harsh, its earth and water resist his attempts, and he finds poor rest amongst tree branches. Exhausted and futile he enacts his uncertain life, watched by a low, cold Sun.

This is an effective pairing of exhibitions to demonstrate the powers and proneness of Yang Fudong’s highly refined practice. “Close to the Sea” is thick with an impotent atmosphere, its human situations flowing endlessly at the center; this, coupled with the briny setting bring to mind Tartarus, impelled to pour water into vessels with holes in them which will never fill. “The Revival of the Snake,” however, far better marries Yang’s lingering cinematics with human plight — away from the smooth faces and crumpled egos of his other characters, this searching soldier is an affective case — part of the bare, non-silken side of Yang’s output seen most extremely in “East of Que Village” (2007). It is a vein away from which his more recent work has tended, but which one hopes may continue.

2012.06.25 Mon, by Iona Whittaker Translated by: 顾灵 Check out Randian website here

Back to Index

Back to Index