Anachronism in Contemporary Political Art

The classic quote by Karl Marx goes: “Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.” Such satire is not only appropriate in reference to Napoleon and his nephew, Napoleon III; it lends application to virtually all instances of repetition and imitation in the course of history. Recent political incidents in China and their similarity to events in the past are proof positive of this assertion, regardless of the manner of their repetition. The recent politically themed exhibition “Pessimism or Resistance?” at Taikang Space took audiences into what seemed almost a glitch in the time and space, because no dates were marked on any of the pieces. Typically, such omissions are not serious in exhibitions of contemporary art, where issues of provenance and verification of age do not come into play. In comparison to ancient works of art, contemporary art is relatively “young.” However, with regards to this exhibition in particular, the absence of dates is conspicuous.

At least in relation to this exhibition, era can be used as a starting point when attempting to garner an understanding of politically themed works. In an analysis of the works on show, we should not only take into account the types of visual or conceptual resources available to the artists at the time, or their methods of expression, and the political environment they lived under; we should also consider how the works were received by the audiences of their disparate time periods. The omission of dates in this exhibition does not appear to be an oversight, because the structure of the show is not chronological. The show is separated into five very “of-the-moment” categories: “spiritual axis”, “great portraiture”, “the everyday and the collective”, “rehearsal”, and “local affiliation and international imagination”. Whether intentional or not, time has been cut out of the equation. The exhibition featured works by 27 different artists; in addition to the physical works on show, audience members could also scan two dimensional QR codes printed on the walls to virtually access other works. Artists represented in the show spanned a range of generations, from those born in the 50s to ones harking more recently from the 80s. In other words, when the show’s earliest piece (Wang Guangyi’s “Mao Zedong – Black Grid,” 1988) was completed, the youngest artists featured in this exhibition were only five to ten years old. Case in point is Wu Junyong, born 1978. Coincidentally, Wu’s piece also happens to be a portrait of Mao Zedong; the two pieces seem to hail from the same contextual period, leading the audience to have the illusion of travelling through time.

Therefore, a more meaningful interpretation of the exhibition purposefully bypasses the curator’s image-based categorizations of the works, and seeks out coordinates of time. If we take a closer look at Wu Junyong’s piece, we will see he has taken a literal interpretation of the Chairman’s family name – Mao or “hair”, and painted him as a hirsute monkey sitting on a wicker chair in a presidential pose. It’s not necessary to debate the artist’s intention in this piece, as there are numerous precedents of artists manipulating images based on semantics. Rather, over the last 30 years, there have been numerous artists who attempt to gain some legitimacy by using Mao’s image. Perhaps, this is partly why artists today continue to focus on a subject which has nothing whatsoever to do with their personal experiences. According to the curator, the title of this exhibition is a question being asked of the audience: pessimism or resistance? Although the title seems to be a simple choice between two options, in fact, it is not; rather the title itself is where the true debate lies. It is similar to the duality of “democracy” and “autocracy”, the key is to examine who is affected. Whose pessimism? Whose resistance? Perhaps this title of this exhibition evokes a similar feeling to Lu Xun’s famous saying “Unless we burst out, we shall perish in this silence.” In the end, pessimism, resistance, such experiences and inspiration art brings to the viewer, and even the messages conveyed are not important. What is truly important is this: who are the people interested in politically charged contemporary art? The question is easily answered when viewing each individual work, because they are all a product of the way in which the artists approached the theme of politics at specific points in time. No matter how the artist chose to enter their works into the market and the public eye, or what materials they used, the choices they made in the process were within their prerogative as artists. However, when attempting to group together 20 years of political works into one exhibition, the challenge must be acknowledged — the difficulty of such an undertaking would be even more obvious if the pieces were marked with dates.

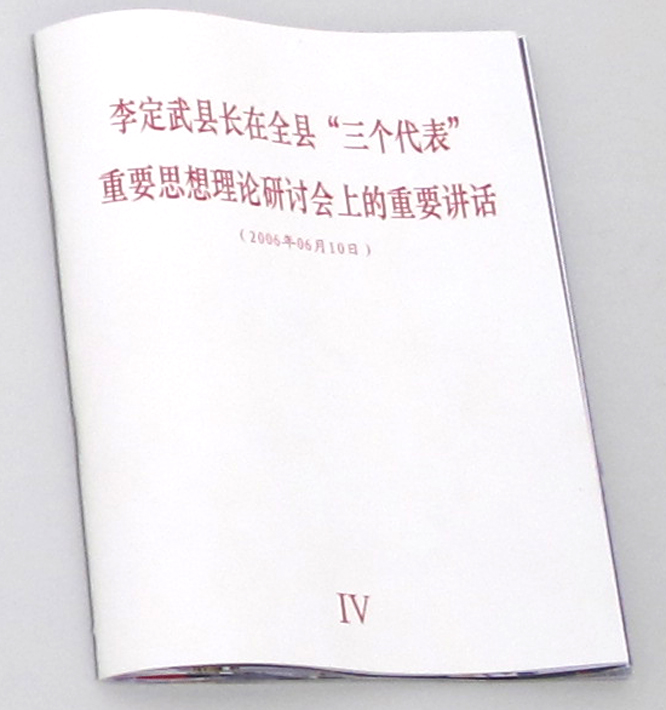

Admittedly, this exhibition definitely does not fully represent contemporary art; it is a microcosm of Chinese art with political themes. A clear trend emerges when comparing current political art with works from 20 years ago — the usage of media technology is becoming more common. If Wang Guangyi’s juxtaposition of Mao’s image with symbols of popular culture also incorporates his personal experiences on the work, then “post-80s” generation artist Ge Lei’s 2006 work “Conference History” only presents an online experience without a personal element. The artist collated various photographs of conferences found on the internet and printed them in an archetypal conference pamphlet entitled “Important speeches by county magistrate Li Dingwu made at the county-wide seminar to discuss the important ideology and theory involved in the ideology of the ‘Three Represents’”. The work attempts to penetrate the bureaucratic and formalistic nature of Chinese politics by deconstructing them at the most basic level – the county. However, the intended recipient of the artist’s pamphlet is a mystery to the audience. Pingyao, an ancient city oft-visited by tourists in Shanxi province did convene an educational session on the “Three Represents” ideology in 2005, but in reality, such conferences and sessions are as common as sand on a beach. For most Chinese people, such commonly heard phrases as “The leader spoke this and that,” “Understanding the spirit of such and such mentality,” or “such and such conference was victoriously opened or closed” fall on deaf ears because of their pervasiveness in mainstream media. Therefore, when the artist insists these conferences have anything to do with our daily lives and personal experiences, their only effect is to give us a sense of the increasingly oppressive mechanization of politics. In effect, expressing the mechanization of the system through the conduit of contemporary art fills a kind of cultural psychological gap rather than a political one.

In comparison, Xu Zhen’s 2006 performance/video work “18 Days” has more wit, but does not necessarily possess more depth (if depth is even the goal here). The video records the artist weaving through Chinese border monuments in a toy tank, “invading” foreign territories in an extremely amusing manner. The concept of territory is certainly political, which is also why the piece was chosen for this specific exhibition, but Xu Zhen’s work is even more media-oriented than “Conference History.” Rather than reflecting artistic value, it’s more apt to say the work incorporates media value. In the political sphere, territory is really a matter of normalization, but the question of territory can also be applied and discussed, based on particular needs of the moment. It can be placed in the public discourse by media outlets to trigger heated debate, and fan the flames of nationalism. But Xu Zhen’s work does not touch on these issues, and though his “invasion” of foreign territories in a toy tank is cleverly thought out, it lacks the depth necessary to inspire profound contemplation in its viewers.

Tanks, portraits of Mao, and Tiananmen form the trifecta of political subjects which contemporary Chinese artists focus on. This is not because they are somehow culturally or politically relevant to our current lives, but because they are viewed as fixed icons on the art market, and are repeatedly produced and consumed. This is why “pan-politicalization” has become an observable phenomenon in the art scene, but the images used to express political themes have barely changed. It goes without saying that politics is (or was) a sort of calling card for contemporary art; without politics, contemporary art is in danger of two things: following a historically demonstrable slide toward unrestricted and unprincipled obscenity of tradition, or being regarded as pure entertainment. But this is precisely where the paradox of politics in art lies: on the one hand, contemporary art marks its position by the coordinates of contemporary politics, but on the other hand, art is also bound by the constraints of political discourse. The passing on of this ever-present trifecta of political images in the contemporary Chinese art scene may well be a long, drawn-out death, much like the long line of of revolutionary, war, or military-themed shows and movies dragging themselves over domestic television and movie screens over the years. Importantly, the reason these images have passed their zenith is not at all to do with censorship or control; they have lost their vitality simply because of their institutionalization. The Cultural Revolution, Mao’s cult of personality, and tanks at Tiananmen were once collective wounds on our contemporary national psyche, but through institutionalization, they have been warped into status symbols, consumerist products, or even tools used in the acquisition of personal wealth or green cards.

However, with the passing of time, the characteristic aspect of Chinese contemporary art has found an opportunity to appear once again: as soon as the political system opens the door even the tiniest crack, they will not hesitate to squeeze their way in. When faced with attractive government projects, Sui Jianguo has never declined, nor has he ever ceased his symbolic ridicule of ideologies. Can the contemporary art of today contend with current issues using present-day methods in the same ways it once contended with the ideologies of the past? If political art aims to maintain its edge, and keep its relevance to the contemporary consciousness, it must exist in the context of the current dialogue. The significance of Chairman Mao in the new millennium must differ from his significance in the 80s and 90s. Similarly, Tiananmen and those iconic tanks must also inhabit a different range of implication and meaning. If the works are largely reproductions of their forbearers; they will never affect history, and we will never witness the self-reflection present in the works of “classic” avant-garde artists like Wang Guangyi or Huang Yongping.

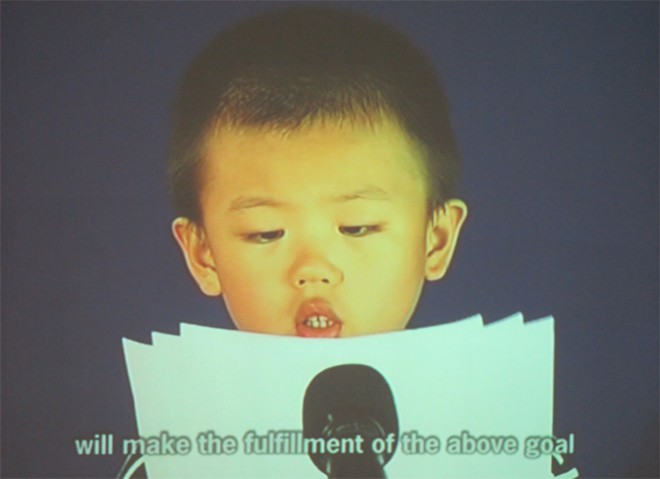

“Anachronism” causes us to view ideologies as historical. In addition, the political themes re-appearing in art become rhetorical tools which can be used again and again. In other words, once the vocabulary of a certain ideology is established, a corresponding visual ideology will also be born. In reality, China’s activity in the Avant-garde movement only takes up an instant when taken in the context of the movement’s entire history – especially if we only include the Avant-garde works made in or reliant upon academies or institutions. In fact, they are better suited to Peter Bürger’s definition of “Neo-Avant-garde” – merely imitators and followers of the historical Avant-garde movement (the names of members of the early underground cultural/artistic groupings like “Stars” and “Wuming” were conspicuously absent from the exhibition). They imitate the different voices in the crowd, but the system has never lacked voices to mock them, and it has never lacked methods of silencing these voices. The system can use cultural and financial mechanisms, or exercise controls over exhibitions to quiet these voices. It can continue to bring their messages into the mainstream through manipulation of the media, causing the true political meaning of these messages to become faded and impotent through repetition. For example, when comparing Li Songhua’s 2005 work “Keynote Speech” with Zhang Peili’s 1992 work “Water: Standard Version from the Ci Hai Dictionary,” it is difficult to determine how their object of ridicule has changed. However, seeing these two works together (the latter via a two-dimensional code) provides an even more scathing satire.

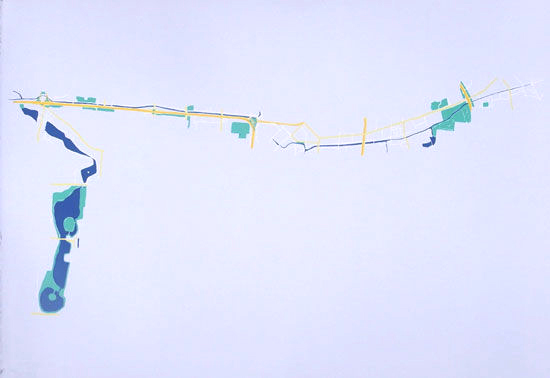

Of course, this does not imply the total lack of different perspectives from the exhibition; only their voices were slightly weaker in comparison. An example is Xu Qu’s performance piece of two years ago, “Upstream” (2011). Although it was not afforded the best position in the exhibition (placed in an upstairs corner), and the piece itself is not “eye-catching,” lacking all the typical marks of political works, it manages to convey a political experience which is closely linked to our present-day experiences. The piece is a record of Xu Qu’s journey upstream in an inflatable rubber raft through one of Beijing’s waterways. The work is profound because it does not deviate from the artist’s personal experiences, but still manages to create a visceral and painful friction by interacting with the effects of the system. Just as Xu Qu explains, “We can either walk on the broad path of expression, or we can check our ideas into another system. Apart from the expressive ability of words and our bodies, our other modes of expression are devolving. Perhaps this is because we often overlook the things we have divorced from ourselves, or because of our unfamiliarity with each other, or the sense of distance that comes from living in a city. Our various incapacities have trapped us. Whether we seek self-realization, or make political appeals, in the end we find ourselves defeated by the reality of the system.” In other words, what political art currently lacks is not ideological opposition, or manipulation and misappropriation of images, and certainly not media attention – what it lacks is the link between politics and individual experience.

When a certain political consciousness has passed on, why do its representations insist on lingering? Because at its core, much of so-called “contemporary art” is in fact made of the very same stuff it claims to ridicule, attack, and satirize.

“Pessimism or Resistance?” Group show with: He Yunchang, Song Dong, Lu Hao, Zhao Zhao, Xu Qu, Ai Weiwei, Jiang Zhi, Wu Junyong, Li Songhua, Wang Guangyi, Wang Jin, Polite-Sheer-Form Office, Mao Tongqiang, Ge Lei, Sui Jianguo, Yang Zhenzhong, Li Songsong, Jiao Yingqi, Hu Xiangqian, Qin Ge, Song Ta, Zhen Guogu, Xu Zhen, Liu Xinyi, Shi Wanwan, Zhou Xiaohu, Huang Yongping.

Curated by Su Wenxiang.

Taikang Space (Caochangdi Red No. 1-B2, Cuigezhuang,Chaoyang District,Beijing, 100015) Apr 20–Jun 8, 2013

2013.07.09 Tue, by Liang Shuhan Translated by: Fei Wu Check out Randian website here

Back to Index

Back to Index