MOMENTUM AiR

STUDIO RESIDENCY

Mahsa Foroughi

15 June – 15 November 2022

ARTIST BIO:

Mahsa Foroughi is a published Persian poet, filmmaker, critic and architect. She was awarded her PhD for interdisciplinary research on architecture, film and philosophy that questioned the status quo of humans’ perception. As an academic, she has been teaching architecture history and theory at UNSW since 2018. Mahsa is one of the authors of The Theatre Times, a non-partisan, global theatre portal. Mahsa has recently been offered an artist residency in Berlin to develop and produce her docudrama A Poetic Suicide. She has also finished her first non-fiction book, Haptic Visuality in Arts. She previously engaged with the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), National Art School (NAS) and Carriageworks as a literary curator’s assistant.

ARTIST RESIDENCY PROJECT:

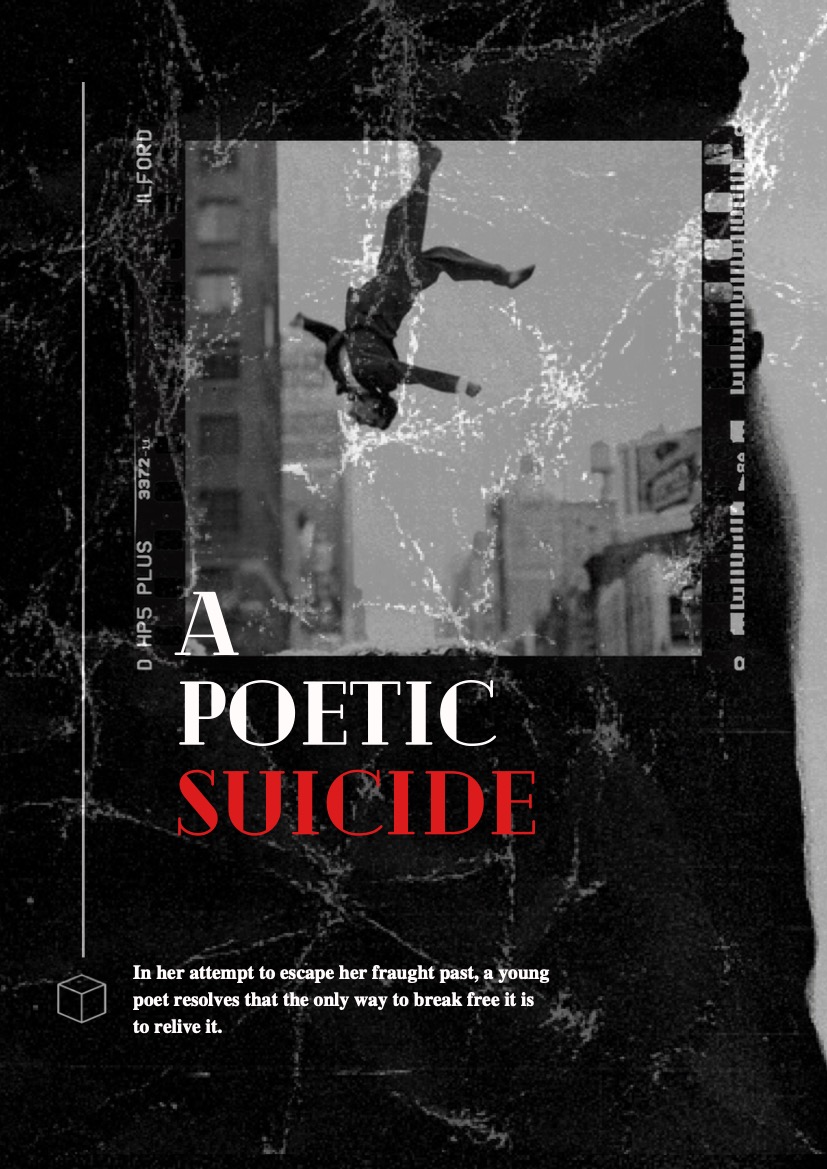

A POETIC SUICIDE

For her Artist Residency project at MOMENTUM, Iranian filmmaker and poet Mahsa Foroughi undertakes research for the production of her new film, A Poetic Suicide. Set in three seminal cities spanning three continents – Tehran, Sydney, and Berlin – this work commingles the bitter truths of history and the poetic license of fiction to address individual and collective memory, trauma and healing, dream and reality. Based on a young poet’s life in post-revolutionary Iran, and then in Europe and Australia, A Poetic Suicide explores a young girl’s attempt to escape the trauma of persecution through an inner journey taking her to her most terrible memories and fears. The film traces the poet’s growth from a rebellious teenager in Iran to a desperate young woman in Australia, and onwards through her family connection to Berlin. Shot on location and also using found documentary footage, this film is designed as visual poetry comingling historical fact with fictional dreamscapes.

[fve] http://player.vimeo.com/video/716457757 [/fve]

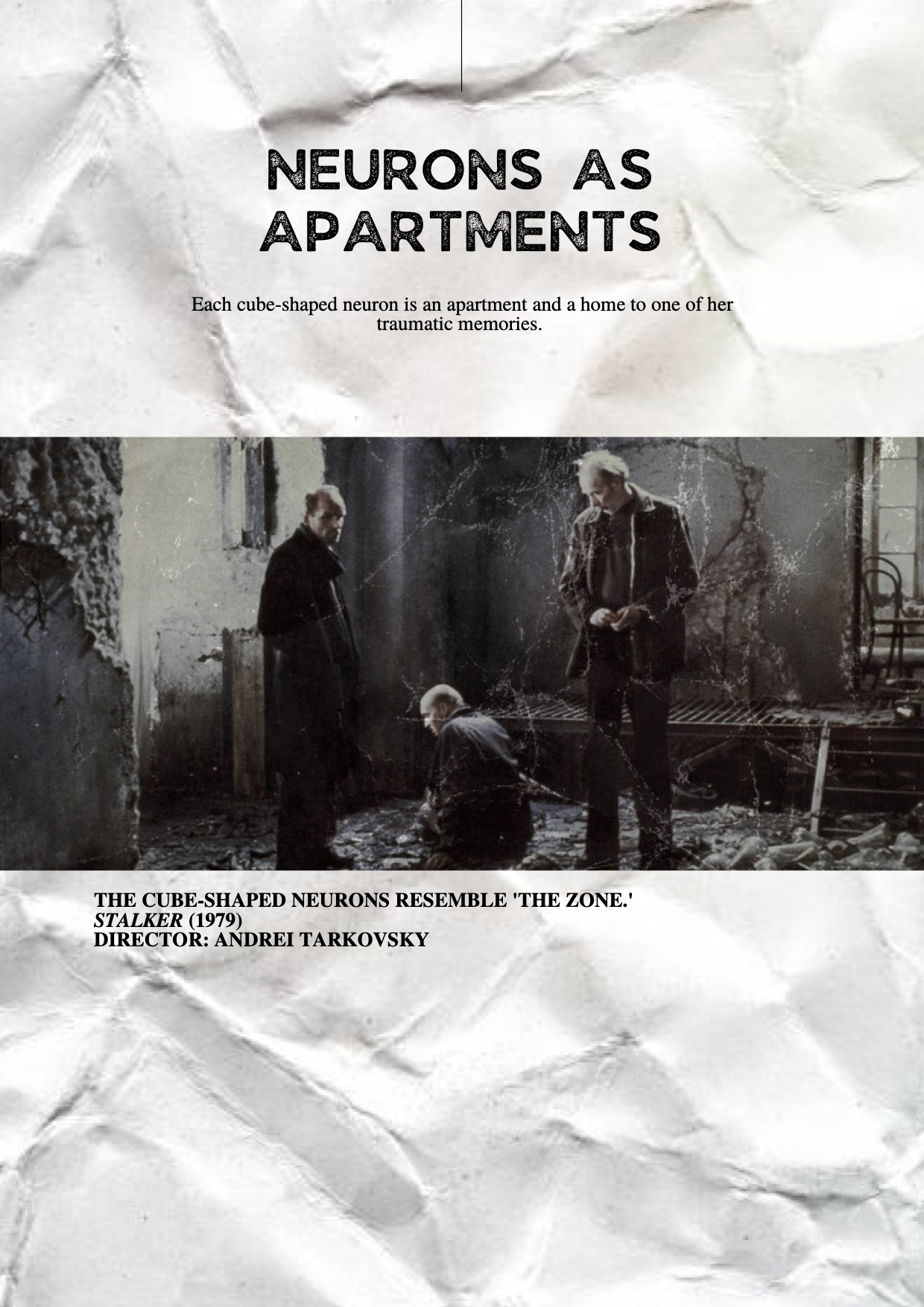

“What if I told you that instead of ordinary round neurons, the poet has a head filled with concrete cubes, each holds an embodied memory? What will become of people like her? The disillusioned poet and her cynical cameraman take us on a spiralling inner journey. A mysterious, baffled, and woeful voyage to the poet’s brain who tries to escape the trauma of persecution. She is no Don Quixote! Nor has she lost her mind! She simply desires to reveal the truth, the one that exists in the liminal space. The space we all experience inhabiting at least once in our life. Yet to reveal and revive such truth, we must hold on to poetry and swing between dream and reality, fact and fiction, verity and myth.”

– Mahsa Foroughi

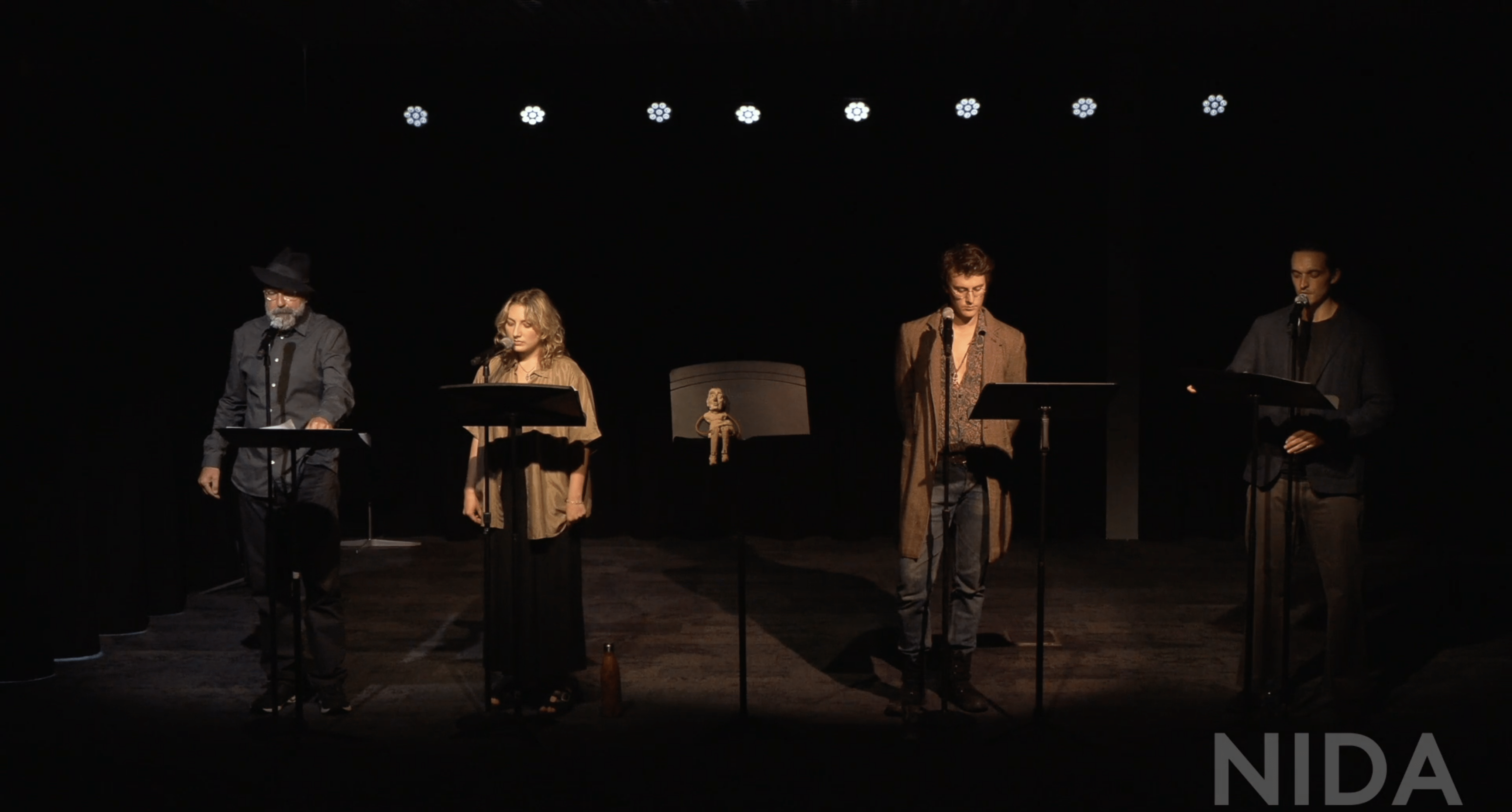

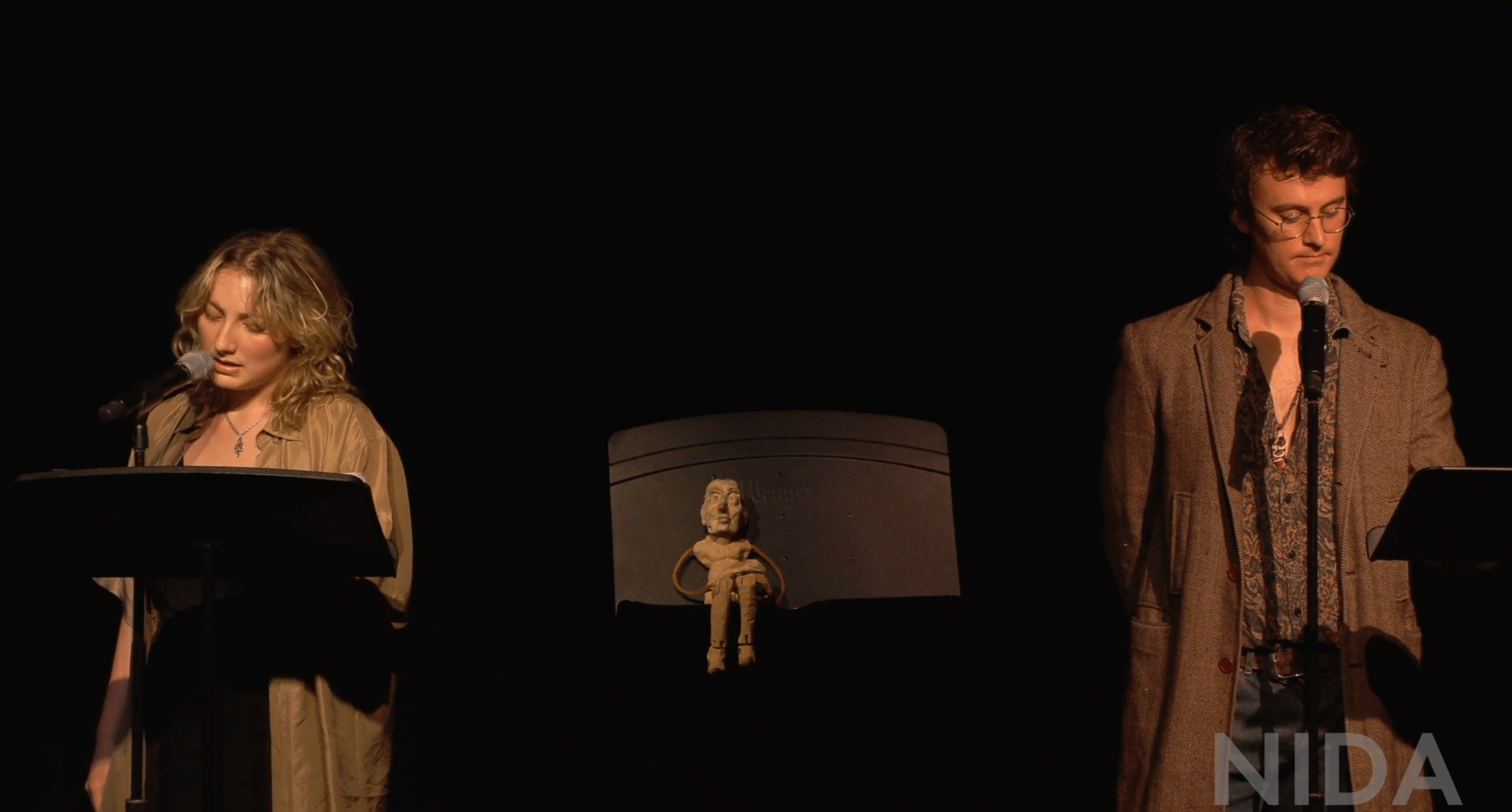

WATCH HERE “A POETIC SUICIDE” READING PERFORMANCE >>

ARTIST STATEMENT:

Poetry, pain, and the memory of grandma’s cushion-cut agate ring

My dream of living a poet’s life has been significantly influenced by developing a cinematic perspective. As an immigrant from a non-English speaking background residing in Australia in my mid-twenties, I have found it challenging to communicate poetry through literary form in English. The task of translating poems from Persian to English does not do any justice to the inherent essence and highly stylised poetry forms I have been pursuing in Farsi. Yet cinema has provided a way for me to overcome this obstacle.

Cinema has always been my second – if not first – favourite art form besides poetry. The slow, meditative, minimalist cinema of Andrei Tarkovsky, Be ́la Tarr, Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Alexander Sokurov and Abbas Kiarostami has always been of inspiration; to observe how these filmmakers steer away from the plot to focus on poetic consciousness and life itself. In sharp contrast with mainstream commodified entertaining cinema, these filmmakers use poetic drives and slowness as instruments to explore everyday life, using high culture and literary exercise to convey the beauty of language while challenging our moral, ideological and existential conventions. Within this context, I set a goal to use cinema as a means to write a form of poetry that could illustrate a tranquil sense of slowness that in itself offers a much stronger message.

My interest in philosophy was another drive for creating a script that explores the question of personal memories versus history. If memories are experienced subjectively, and history is written objectively, what is time? Is it an objective, linear measure of our lifetime? If so, why have our memories always returned to us in a non-linear fashion? What is this unconventional juxtaposition of the past and the present? The French philosopher Henry Bergson postulates a theory that time is a duration that involves a subjective account of temporality. According to Christine Ross (2012, p. 23), time goes ‘beyond the measured task-oriented temporalities of daily life.’ Having criticised Immanuel Kant’s view of time as a priori form of sensibility, which exists external to our body, Bergson (1950, p. 232) argues that time is not a homogeneous medium but a pure duration, which ‘is made up of moments inside one another and is dependent on the individual experience.’

John E. Smith (1969, p. 1) explains that the questions relevant to time as a quantitative measure are ‘How fast?’, ‘How frequent?’ and ‘How old?’, whereas time as a qualitative sensation point to an experience that happens at a specific moment, that would not be possible at another time and under other conditions. My memories, their traumatic nature, and their recurrence in my present life led me to consider time as a durée that is inseparable to discrete moments, while constantly referring to the past that ‘incessantly prolongs itself into the present’ (Ross 2012, p. 23) so that the present is co- perceived with the past. When I started writing the script, I was in this headspace; to show the subjective ground of time or time that is experienced as a significant moment. I was not sure how to deliver such subjectivity. Still, somehow, unconsciously, I picked a form of docudrama, the documentary exploring objective chronological traces of historical events and the drama delving into the non-linear chaotic personal memories. In this comparative context, I realised that the subjective approach to time involves a qualitative character that could better be addressed through our haptic perception rather than our visual faculties. This meant a multi-sensory approach was crucial to my exploration of personal memories.

In its ancient Greek etymology, the term haptic (haptikós) means ‘able to come in contact with’, which derives from the verb haptō, which means ‘to touch’. Haptic perception is then a perception that, by drawing on all sensory experiences, equips us to grasp and touch an event, a story, and untouchable memory. These thoughts brought me to A Poetic Suicide, a film that I drafted and redrafted many times to further explore the nature of traumas. During my writing, I drew on the thematic, aesthetic and textural qualities in Tarkovsky’s movies, which offer representations that evoke senses other than vision by depicting alternative modes of knowing that prompt memory. However, my script differs from Tarkovsky’s cinematic style by employing a type of docudrama instead. I rely on documentary conventions to represent people’s struggles in Iran and other parts of the world—those historical moments that are otherwise repressed and erased from the official or popular memories.

On the other hand, I use drama to evoke a form of literary exercise and illuminate life’s sophistication and the complexity of pain. Through a voice-over recitation of various poems (each corresponding to the event explored in a particular scene), I bridge documentary and drama to put the audience on the edge of dream and reality, fact and fiction, truth and myth. The film I aim to make is an invitation to feel rather than follow, experience the imperfect world, perceive human pain and recognise that a wound is a wound: it hurts no matter our skin tone, place of birth, language, race or gender.

Writing Process

An inspiring in-class experience sparked this project’s beginning. We were asked to draw on a method of free-associative writing, which in essence means writing without thinking. This task is not the easiest since the unconscious goes to its darkest memories and digs out dirt and traumas that sometimes are not safe to explore without supervision. However, in this process, I touched on and brought to focus my deepest concerns in the most poetic form. The script begins by exploring my past

experiences in Iran and Germany, tracing the life of an immigrant poet who tries to escape the trauma of persecution for her political beliefs and sexual identity by travelling to what she hopes will be the freedom of the West, only to discover a brick wall of incomprehension that makes her feel even more alone than she was.

Having read Laura Marks’ book The Skin of Film over the past year, I believe that the condition of being in-between cultures lets intercultural filmmakers use sensations over visual glamours in the search for ways to represent embodied speculations and experiences of people living in the diaspora: ‘Intercultural cinema moves backward and forward in time, inventing histories and memories to posit an alternative to the overwhelming erasures, silences, and lies of official histories’ (Marks 2000, p. 151–152). The condition of living between two or more cultures, with the host culture as a dominant narrative, prevents intercultural filmmakers from representing their memories and experience in the dominant idiom1. Therefore, the use of silence and the omission of the visual image is a way for intercultural filmmakers to explore new forms of expression. And so it does for me; I wrote A Poetic Suicide during my life in Australia, feeling uneased here and there (in Iran), to find alternative modes of expressing my memories of pain and trauma. I am trying to avoid these official records of history (what the West wants to see from the East) to focus on the characters’ feelings or personal relationships to the past. Just as Tarkovsky directs us to imagine the faith of the character who is removed from his home, A Poetic Suicide draws on universal genocides to reveal the private and ordinary memories that are located in the gaps between the dominant narratives of history: the untruthful account that stays away from poetry, pain and the memory of grandma’s cushion-cut agate ring.

Work Cited

Bergson, H 1950 (1910), Time and free will: an essay on the immediate data of consciousness, trans. FL Pogson, George Allen & Unwin, New York.

Marks, LU 2000, The skin of the film: intercultural cinema, embodiment, and the senses, Duke University Press, Durham.

Ross, C 2012, The past is the present it’s the future too : the temporal turn in contemporary art, Continuum, New York.

Smith, JE 1969, ‘Time, times, and the ‘right time’; Chronos and Kairos’, The Monist, vol. 53, no. 1, p. 1–13.

Back to Index

Back to Index