|

FIONA PARDINGTON

Fiona Pardington’s work investigates the history of photography and representations of the body, examining subject-photographer relations, medicine, memory, collecting practices and still life. Her deeply toned photographs are the result of specialty hand printing and demonstrate a highly refined analogue darkroom technique, translated in her more recent practice to digital media. Of Ngāi Tahu, Kati Mamoe and Scottish descent, Pardington’s practice often draws upon personal history, recollections and mourning to breath new life into traditional and forgotten objects. Her work with still life formats in museum collections, which focuses on relics as diverse as taonga (Māori ancestral treasures), hei tiki (greenstone pendants) and the now-extinct buia bird, calls into question our contemporary relationship with a materialized past as well as the ineffable photographic image.

Pardington holds an PhD in photography from the University of Auckland and has received numerous recognitions, including the Ngai Tahu residency at Otago Polytechnic in 2006, a position as Frances Hodgkins Fellow in both 1996 and 1997, the Visa Gold Art Award 1997, and the Moet and Chandon Fellowship (France) from 1991-92. Born in 1961 in Devonport, New Zealand, Pardington lives and works in New Zealand.

Pardington participated in MOMENTUM’s 2011 exhibition A WAKE: Still Lives and Moving Images with 30 digital photographs chosen from three discreet series of works, now organized into the single moving image piece “Organic” (2010/11) for the MOMENTUM collection. By pairing seemingly random but personally charged items that once belonged to beloved family members in New Zealand, she questions the nature of human survival in relation to forgotten or altered cultural activity.

In 2014 Fiona Pardington undertook a seven week Artist Residency at MOMENTUM, working towards her participation in the exhibition FRAGMENTS OF EMPIRES (7 Nov 2014 – 1 Feb 2015).

“It works on a number of levels – once again my whakapapa/genealogy – random items that belong to beloved family members and important family members i had little contact with – like a child’s silver christening cup found by chance in a skip by my aunt when my grandmother’s house in bluff, southland was cleared after sale – it belonged to my father…silk scarves found in french flea markets, shells taken from beaches important to ngai-tahu because they are mahinga kai/traditional food gathering from the sea….seaweed, bottles dug out of the sand, hidden shells from the beach the ngai-tahu cheif tangatahara lived near. Paua shells from otakou – paua shells are important food but also the shell can be seen as a tourist cliche and is sitting in a strange NZ cultural limbo presently. Crystal wine glasses from op shops, native flowers and introduced weeds and pest plants introduced from overseas by the colonizers.

All the flowers and fruit are found on waiheke on roadsides (one of the few places wild food still exists on our waiheke) and back yards, or my back yard (very early house) or abandoned houses/fields. Op shops around NZ for much of the glassware/junk- or france, same. Many of the objects are mine personally, each with particular meanings/memories and places. I see reflections of the original cultures colonizers were a part of. There are personal simple lifeways in things such as agee jars and early penfolds wine/sherry bottles. Some of the bottles are dug up from early settlement is NZ like out on the otakou peninsula. Pipi and shells from traditional maori food collection beaches both here and otago/moeraki… weeds like hemlock, wormwood/mugwort, clover, etc etc…potions, healing, poisoning, folk remedies. I have yet to do clematis and a few more maori plants involved in rongoa. soon as rose season comes, theres early settlers roses that have gone wild to pick and photograph. eggs are from my freerange chickens. They tie you to nature, going and picking up warm eggs just laid. Also such a perfect meld off form and function is the egg. the big one is a hand made dummy egg – it was made by an old lady on wilma road who has organic goats, makes cheese etc – raku fired and blue (for my aracana hens) she gifted it to me when I gave her some of my laying hens.

Huge woodpigeons eat all the plum blossoms and the new leaves. All the weeds and such have their times to blossom, I’m watching seasons as I drive up and down to the ferry, watching individual plants of hemlock bud flower and seed. Lemons – nothing more beautiful than the morning scent of a lemon picked by our own hand from an ancient bush. They are all lumpy and have various leaf blights and so forth, but they are so real, matter of fact.

Survival, seasons, bottling, making jam, its all activity lost to many of us. It was more than a good quality of life, it meant the difference between struggling and starving or living with some grace and gusto.

My grandmother told me that when she was young, she and her mother dug a big pit on their back yard and buried all their unwanted crockery and glassware…. there’s an old fridge buried in this back yard. An old chicken coop has been broken and smothered by a huge plum tree. A staple fruit tree for early NZ colonizers. Jam pans in the shed. Bottling jars. I still fantasize about finding the house and the backyard and digging up all my great grandmothers unwanted kitchenware. people did things differently back then.

I spend a lot of time on beaches and on land surrounding beaches looking at the shells, fish, food sources, the power of one pipi shell (herries beattie collection at dunedin public art gallery taught me that, as any maori about their mahinga kai) ……where people lived and what they planted, what they cut down and destroyed, remnants. Like old bottles and jars. Things dropped and lost. Gorse. Gorse gorse….one of my next still life subjects. It was hedging in britain but flowers 4x a year here. It really upsets me. Pipi shells have different striations and colours depending on the minerals they are buried in. I know where all the different coloured shells – blacks or oranges – are on different beaches, and where certain types of shells I love are. I know their names and they comfort me and keep me focused when I am thinking about art when i walk on the beach. I find them each so unique and so humble, little bits of nothing, but each nothing is also something. Everything and nothing combined. Just like me, or you.

People getting old and dying, all their things been thrown out in to the bush behind their house, left in sheds or sold, given to op shops etc…its just happened to one of the original pakeha families 3 doors up – house sold, all their stuff gone, found his 1930′s drivers license in the bush just up from our place. Someone had thrown all their old suitcases down in to the creek in the native bush below us. Masses of baby nikau and karaka seedlings slowly suffocating them. Fallen widowmakers (epiphytic plants living in the top of tress that fall down and kill people) lying dying on the forest floor. Trickling water and tui song chucking away out in the sunlight. I know there are morepork hiding and there is a white kereru in the valley.

Every object has a particular meaning for me, a certain feeling, an emotion, a history, often a history I can sense, even though I can’t tell you its story.”

— Fiona Pardington (2011)

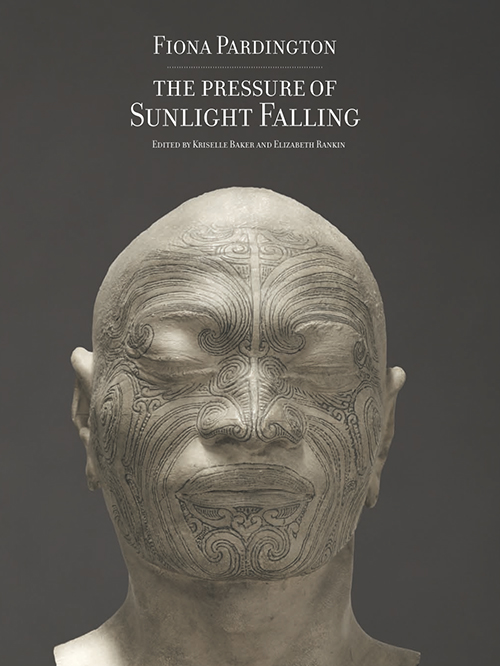

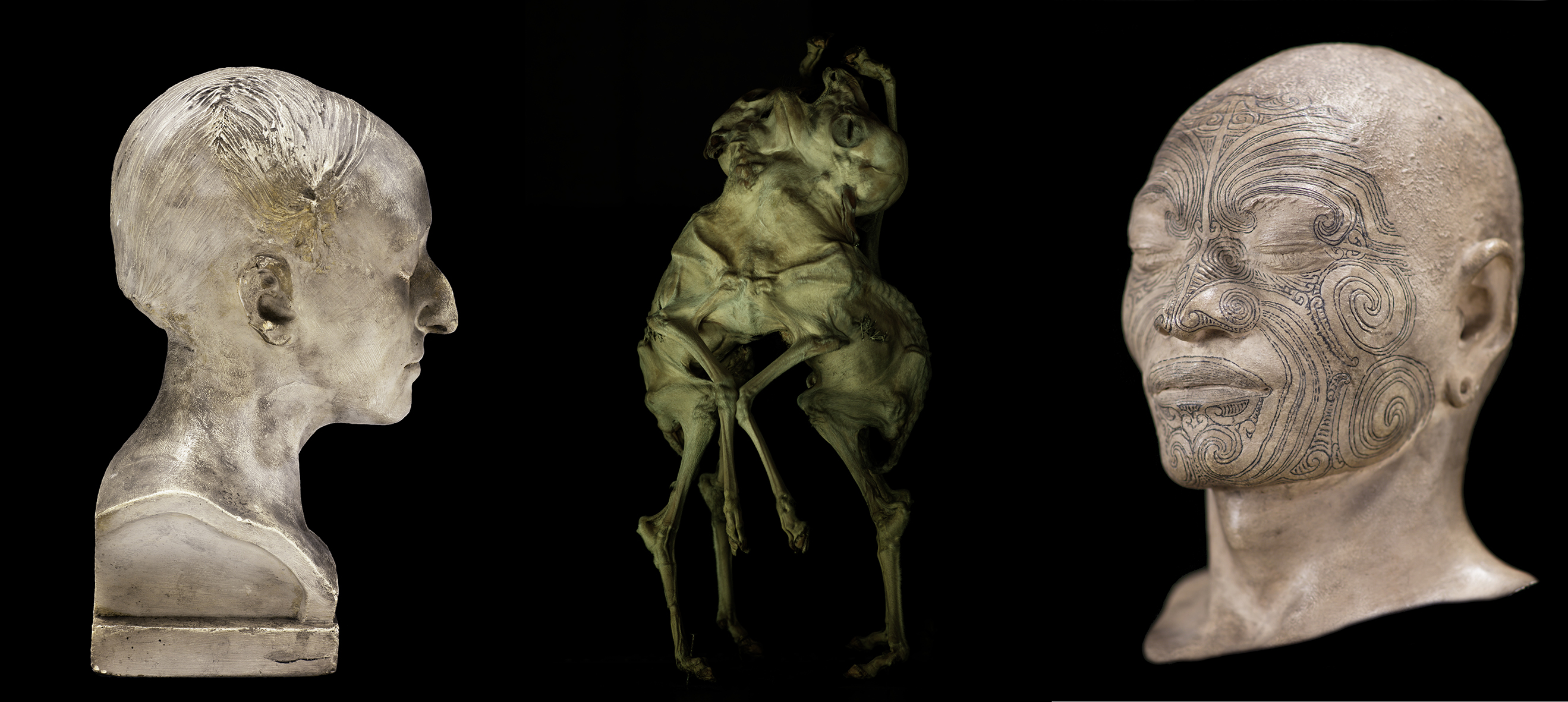

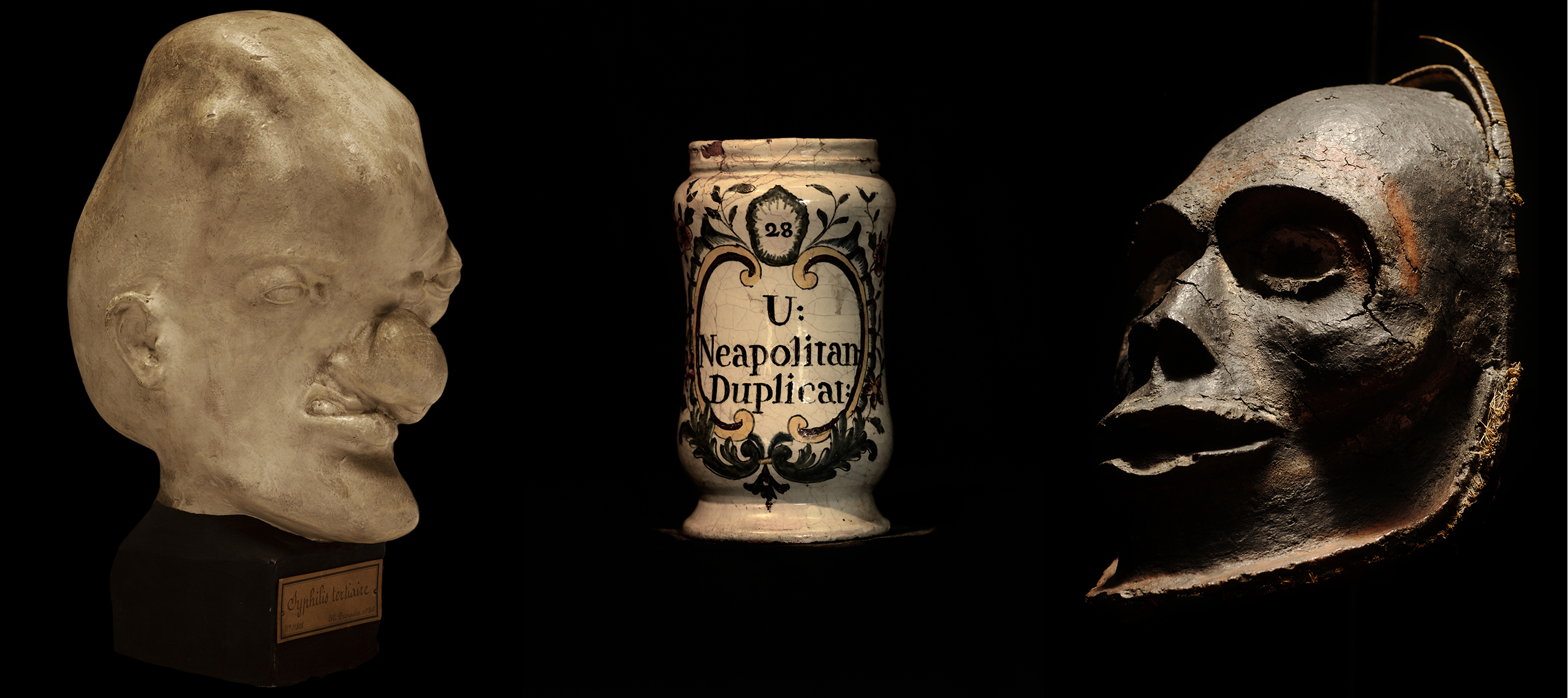

Quai Branly Residency, 2010

This series was made during Pardington’s Residency at Musée Quai Branly, Paris (Résidence PHOTOQUAI) in 2010, which she pursued as an extension of the work she presented at the 2010 Sydney Biennale (Ahua: A Beautiful Hesitation), for which she created a series of large-scale portraits of life-casts made of Maori and Pacific peoples during Dumont d’Urville’s voyage to the Pacific in the mid-19th century. This led her to further her research and exploration of the rich and equally controversial archives of French national collections and most notably those housed at the Musée de l’Homme, in Paris. Taken from both dead and living models, the resulting casts can be understood as early precursors to photography – a mechanism through which to achieve an allegedly exact, indexical recording of a subject. Similarly, photography – invented only about half a century after these casts were made –immediately became an instrument of ethnographic studies and thereby embodies a thoroughly problematic genealogy of its own. In this series, Pardington explores the presence of the subjects that were forever captured in the casts with the utmost degree of respect, thereby endowing the photograph with a profound sense of humanity, of which its history once robbed it. Simultaneously, she inverts the direction of the gaze: it is now not the colonized, but the coloniser’s view of the colonized that becomes thoroughly scrutinized. Largely abstaining from a straightforwardly judgmental approach, however, Pardington rather attempts to understand how or why it was so impossible for the colonizer to integrate with those who appeared so alien to them.

— Isabel de Sena

Still Lifes, 2011

With a clear reference to the (Dutch Golden Age) still life genre in painting, this series is a bold challenge to much of contemporary photographic practice and its preference for highly Photoshopped and stylized imagery. Pardington’s still life photography has an extraordinary painterly quality and she dedicates much of her diligent attention to meticulously arranging, lighting and capturing the objects, rather than on working the digital images in the post-shooting phase, which, though she does not discard it altogether, she does limit to an absolute minimum. Like a painter, the quality of the image-surface is of utmost importance to her and from her classical training in the time that analogue photography was widely practiced, she became a highly skilled master of fine photographic hand-printing. Today, faced with the kind of plasticized papers and synthetic substrates that the industry produces, Pardington has turned to photo-prints on canvas in the last decades. Not fully satisfied, however, and unremittingly insistent on the importance of the image surface, Pardington has embarked on a complex period of research that has led her to invent a new photographic substrate and is currently setting up an industrial studio to produce it, based in Auckland. This substrate is ground-breaking in that it allows for a remarkable amount of detail on an extremely smooth surface and retains its prime condition even after rolling the canvas.

Ultimately, the weight that Pardington awards to the photographic image-surface bears on her intense preoccupation with the immediacy and immanence of the image. Weary of the distance that a glass-covered and/or plasticized print builds in relation to the viewer, Pardington insists on maintaining a strong presence in the nature of her photographic images and by extension of the subjects depicted in them. Fundamentally, the animistic Maori tradition, furthered by the influence of Gilles Deleuze’s writings on the plane of immanence (the central concept of her doctoral thesis, ‘Towards a Kaupapa of Ancestral Power and Talk’, University of Auckland, 2013) greatly inform her particular relationship towards photography. This series’ reference to the Vanitas-genre (remember death and the meaninglessness of earthly life and transient nature of all earthly goods and pursuits, or: “Vanity of vanities; all is vanity”) hereby becomes discrete; Pardington continuously oscillates between life and death, presence and absence, or a constant tension between the two, whereby they ultimately become thoroughly porous and unopposed.

— Isabel de Sena

Phantasma, 2011

PHANTASMA: CECI N’EST PAS UN CHAMPIGNON

When I was young I spent childish good times in gumboots out in cow paddocks eeling or collecting mushrooms in buckets. The rain, fog, big bulls or the creeping fingers of mists slipping down from the fragrant native bush never dampened my enthusiasm, as mum’s mushrooms on toast beckoned at the end of each adventure

– Fiona Pardington

And all the time they could, if they liked, go and live at a place with the dim, divine name of St. John’s Wood. I have never been to St. John’s Wood. I dare not. I should be afraid of the innumerable night of fir trees, afraid to come upon a blood-red cup and the beating of the wings of the Eagle. But all these things can be imagined by remaining reverently in the Harrow train.

– G. K. Chesterton, The Napoleon of Notting Hill (1904)

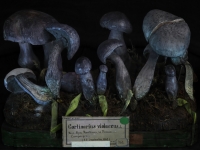

In many ways the Mushrooms: The Champignons Barla series of photographs is simply yet another arrow in Fiona Pardington’s thematic quiver of Eros and Thanatos, the Aristotelian and encyclopaedic collecting policies of the nineteenth century museums, the eighteenth century Wunderkammer cabinet of curiosities, and a pronounced Francophilia. The Musée de l’Histoire Naturelle in Nice, driven by the celebrated naturalist, Antoine Risso (1777-1845), was the first museum to open its doors in that city, in the Place Saint François (the old city square) in 1846. Jean-Baptiste Vérany (1800-1865) compiled its rich collections of birds, molluscs, minerals and fossils, but of interest to us is the private collection of plaster and wax models of fish, flowering plants, and especially fungi of the South of France by Jean-Baptiste Barla (1817-1896). Barla’s collection became part of the museum in 1863 when it moved to its own premises on the site of the current museum, donated to the City of Nice in 1896. It was here on a visit to Nice in April 2011 that Pardington discovered the mycological collection and photographed it for four fungus-filled days.

It is only natural that a culinary culture like the French would be fascinated by fungi. The playwright and satirist Molière named his most famous fictional creation Tartuffe for the old French for truffle, and even named his country estate “Perigord” for the region in France where the black truffle grows. The French invented the cultivation of mushrooms, growing them in the limestone caves at Bourré in the Loirre Valley since the reign of Louis XIV. Every regional cuisine of France uses its own locally growing fungi: truffles, champignon de Paris, channterelle, pleurote (oyster mushrooms), and cèpes (porcini). If you can eat it, the French probably have a sauce that goes with it, and consequently the French know their fungi. The Larousse Gastronomique contains extensive notes on the cooking of mushrooms, and the poisonous ones to avoid. Models like the Barla collection were originally created and circulated around the French municipalities on the typically pragmatic orders of a recently restored Napoleon III so that the public might be educated about which mushrooms were and were not safe to eat.

Among the images of Mushrooms we find a rambunctious cavalcade of names, forms and colours. Each unique specimen is made a character portrait, invested with a personality and supernatural presence as if one had stumbled upon them in some ancient primeval wood. Most of these specimens are poisonous. One of the most deadly fungi of all, though not found among these images, is the Amanita phalloides, the Death Cap or Destroying Angel discovered in 1727 by a French botanist who gave it its Latin name for its phallic appearance rudely jutting erect from the maternal earth. As the common names suggest, A. phalloides is deadly poisonous, and unfortunately resembles some edible mushrooms such as the common Puffball. The fifth century BC Athenian tragedian Euripides lost his wife and three children to a meal of this toadstool. It was used to deliberately poison the Roman Emperor Claudius in AD54 (so that Nero might don the imperial purple) and Pope Clement VII in 1534 to prevent him aligning with France (a few days after commissioning Michelangelo to paint The Last Judgement for the Sistine Chapel), and also caused the accidental death of Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI in 1740.

Mushrooms and toadstools, the fruiting bodies of the fungi family, have long held a peculiar place in human culture and imagination. Some of those which appear in these works are infamous. The white-freckled blood-red cap of the Amanita muscaria or Fly Agaric is notorious for its use by the shamans of many cultures from throughout Eurasia to achieve communion with the divine other realm, though unlike the Psilocybe genus (so called “magic mushrooms” or just plain “shrooms”) they have rarely been sourced for recreational purposes outside of wedding feasts in the Lithuanian hinterland (served in vodka). Among the Turkmenic peoples of Siberia the A. muscaria was first consumed by a shaman and consumed by the rest of the tribe in the much safer form of the Shaman’s urine. A similar practice may have been observed in ancient India, giving rise to the legend of Soma described in the Rig Veda. It has been reported that the Sami sorcerers of Lapland would consume A. muscaria that had seven spots on their caps and claims that it was used by the Parachi-speaking tribes of Afghanistan, and the Ojibwa and Tlicho tribes of North America. It has even been suggested that the Viking Beserkers used A. muscaria to achieve their battle frenzy. The A. muscaria is perhaps the archetypal image of a toadstool (a English children’s argot word, as noted by literary opium addict Thomas de Quincy in his “On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts” (1827), a place where toads were imagined to sit). Arising suddenly from the earth in a season when most other plants are dying, and bearing none of the green of spring foliage, it is easy to see how such an ominous growth would be associated with the magical, the underworld, and the dead – particularly given their frequently poisonous nature.

The abrupt eruption of fungi, particularly in circles, was attributed to shooting stars falling to earth, lightning strikes, mephitic terrestrial vapours, witches, fairies and evil spirits, beliefs persisting in rural parts of Europe well into the nineteenth century. A common folk belief was that dire things would befall any mortal foolhardy to step inside a fairy ring, ranging from being struck lame or blind, or losing one’s way or wits, to being abducted to serve in the realm of Faerie where time moves differently to our world. It was a common rural superstition that cows that grazed in a fairy ring would produce sour milk. The Ivory or Trooping Funnel Clitocybe geotropa is now known as Infundibulicybe geotropa (geotropa deriving from the ancient Greek for “earth turn”). Like misery, it loves company and frequently forms fairy rings – one such being reported in France as a half mile across and estimated at eight centuries old. In ancient Egypt only pharaohs were permitted to eat mushrooms, which they believed were reincarnations of the gods that travelled down from the heavens on bolts of lightning.

This is an association certainly not lost on Pardington:

I loved fairy rings and always made a point of trying to stand inside one on the slim hope of catching a glimpse of a fairy. Being an obedient child, I was informed I should never touch Amanita muscaria, that alarmingly festive creature that that pushed up boldly beneath the arms of dark nested pine trees in a park we lived nearby. Magic was afoot in mushroom season and I was not about to miss it…. I felt close to the earth at these times, endlessly fascinated by its secrets. When I lay on my stomach on the ground and looked closely at the delicate furls underneath the mushroom’s hat, I imagined glancing down to see changelings left by cruel fairies in place of children. The fact I was an avid reader from a very young age meant that I was steeped in fairytales and fairy law, my knowledge extended over Christmas holiday visits to my grandma’s, where I would read her occult Man, Myth and Magic weekly magazines, often scaring myself stiff, at the same time revelling in the power of the unseen, occult worlds and to me mushrooms were the outposts, fairy arena, villages or guard-towers of magical kingdoms and occult territories.

The Flemish painters subtly included toadstools in their depictions of Hell. It is A. muscaria which appears so liberally in picture books of tales collected by the Brothers Grimm, its hyphae baroquely populating the undergrowth of haunted forests full of witches, wolves and menacing anthropomorphic trees. In illustrations from the nineteenth century onward, and in that peculiarly tenacious Victorian genre of fairy painting, they are homes to the little folk, which in more recent times underwent metamorphosis into the more cheerful kitsch incarnation of the Smurf (Les Schtroumpfs in French-speaking countries) village and the giant toadstool (by-product of an extraterrestrial mineral) in Hergé’s L’Étoile mystérieuse (1942), an adventure of boy reporter Tintin later translated as The Shooting Star. One wonders if the Mushroom in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) on which the caterpillar sits smoking who-knows-what in his hookah, was related. Certainly Alice’s dramatic changes in size upon eating pieces of it suggest some kind of hallucination.

The Hydnum auriscalpum is these days known as Auriscalpium vulgare. The original name comes from the Latin auris (ear) and scalpo (“I scratch”) and was bestowed by Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), the “Father” of Latin taxonomy, in 1753 for the fungus’ resemblance to an ear pick. In the model it is posed with a pinecone, it’s usual place of incubation. Also represented here is another of the few fungi named by Linnaeus, Cortinariuss violaceus, the Violet Webcap. The Psathyra corrugis or Red-Edged Brittlestem was once the cause of the accidental poisoning of BBC Wild Food presenter Gordon Hillman, when he was given one instead of an edible variety and then proceeded to drink a beer. Alcohol has a liberating effect on many fungal toxins, and in Hillman’s case resulted in monochrome vision, memory problems and difficulty breathing. Is it any wonder that some societies regard some fungi with awe, as if they might transmit their deadly poison through the air like the evil eye.

The spectacular Clathrus cancellatus is of the foul smelling Stinkhorn family and generally regarded with great superstition and foreboding in Southern France, where it is reputed to grow in cemeteries from the bones of the dead, and cause rashes, convulsions and even cancer. The name Clathrus comes from the ancient Greek for “lattice”, referring to the fungus’ basket-like structure. In the area of the former Yugoslavia its red cousin Clathrus ruber was known as Witch’s Heart. Another Stinkhorn in the collection is Phallus impudicus (imodest phallus, a name bestowed by Linnaeus) which is known for its carrion stench and resemblance to the male anatomy. John Gerard (1545-1611) in his 1597 General Historie of Plants called it the “pricke mushroom” and “fungus virilise penis effigie”, while John Parkinson (1567-1650) in his 1640 Theatrum botanicum called it “Hollander’s workingtoole” – cough cough, nudge nudge, wink wink. Gwen Raverant (1885-1957), the granddaughter of Charles Darwin, remembers roaming the woods of Victorian Cambridge with a Maiden Aunt who would locate the rude fungus by its smell, uproot them, and bear them back to the house and burning them behind the locked door of the drawing room for fear of corrupting the morals of the maids. By contrast, the peasants of Northern Montenegro fed the Stinkhorn to their bulls as an aphrodisiac, and rubbed them on the necks of the bulls to give them strength before bullfights.

The Saffron Milkcap or Red Pine Mushroom Lactarius deliciosus has been eaten for centuries. A fresco in preserved by the ash of Vesuvius in the ruins of the Roman town of Herculaneum depicts this fungus, making it one of the oldest examples of a mushroom known in art. Lactarius viridus (now L. blennius) or Slimy or Beech Milkcap cannot be recommended for the table, though a number of chemicals have been extracted from it which prove to have potentially useful medical applications. The unloved Russula emetica has a slew of names deriving from its emetic and purgative properties: Sickener, Emetic Russula, and Vomiting Russula. It unfortunately resembles edible Russulae and one Sickener mixed in with them will ruin a whole meal. Curiously the British Red Squirrel, little Squirrel Nutkin Sciurus vulgaris, has no such problem with the fungus and has been observed to forage for, store, and eat R. emetic with no ill effects. The Man on Horseback or Yellow Knight, Tricholoma equestre or Tricholoma flavovirens is a tricky customer in that it is widely eaten in Europe, but is in fact poisonous. Named by Linnaeus, the botanical name derives from the ancient Greek for “fringe of hair” and the Latin for “pertaining to horses”. This relates to the fungus’ resemblance to a saddle.

Fungi are so charged with a baggage of meaning and alien looking that they even make their way into Science Fiction. H. G. Wells’ story “The Purple Pileus” (1896) makes a mushroom the muguffin that changes the entire course of a man’s life. Ray Bradbury’s “Boys! Raise Giant Mushrooms in Your Cellar!” (1980) and John Wyndham’s “The Puffball Menace” (1933, essentially a dry run for The Day of the Triffids, 1951) feature enormous weaponised man-eating fungi. Looking at Pardington’s eerie images, one might easily imagine these eldritch organic, biomorphic forms to be intelligent, utterly otherworldly, and quite possibly malign.

Much of the fun in these photographs comes from their false premise. Rene Magritte’s painting The Treachery of Images (La trahison des images, 1928–29, Los Angeles County Museum of Art) depicts a pipe with the inscription “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” – ‘This is not a pipe’. Of course it isn’t a pipe, it’s a painting of a pipe. Likewise Pardington’s images are not fungi, or even photographs of fungi, but photographs of facsimiles of fungi. The images exemplify Jean Baudrillard’s concept of the simulacra as not merely recreations of real things, nor even deceptive recreations of the real; they are not based in the real at all, nor do they hide a reality, they obscure that reality is irrelevant to our existence because we semiotically still recognise these images as fungi. As Pardington notes:

What I love about the Barla polychromed champignons is that these fairy-towers or toad-perches aggravate the incorporeal freedom that the simple materiality of the photograph gestures towards. This freedom imbued in every photographic act positively charges us with its link to the invisible realms of metaphysical thought as equally of any intellectual or scientific ruminations. The photograph always impresses us with its blithe ability to preserve and transmit an intimate physical knowledge of our visible world, although its existence does not necessarily depend on any of the references it springs from. For instance, if I take my photographic portrait, it is not necessarily a correlate of my thought, nor a necessary correlate to my absence, or by any absence of knowledge about any of its situated-ness. Photographs operate anonymously perfectly well, and pouring through the thousands of carte-de-visites at the Vanves fleamarket recently impressed this upon me yet again. When my eyes fall upon the photograph of any of the mushrooms, I imagine Barla’s spade plunging in to the earth, editing out the fairy ring of Russula furcata, activating a kind of transubstantiation where the very this-ness of that day, the haecceity of that day and that hour of September 1862 remains with us thanks to the two styles of time portal that moulage and photography represent to us.

In its own humble way, the mushroom moulage sur vif and its companion photographic portrait can even become an operator in nothing less than ‘a phrasing of history’ (Images in Spite of All: Four Photographs of Auschwitz, Georges Didi-Huberman, University of Chicago Press, 2008, p139), its quiet manifestation shaking down our present grasp on what representation might be…. and what slips in between the cracks in the moulages and settles with a fine aura like fairy-dust is the incommensurable.

Over the years, however, the pigments on the models have changes so that they are no longer scientifically accurate; spectacularly so in the case of the R. emetica. This factor contributes another layer of distance and complexity to what at first glance might be considered a relatively simple body of work. As the artist herself says: “For me it is a very nice undercutting of the scientific drive for arrangement of detailed knowledge and certainty. It adds a further ‘danger’ too, because if you followed the advice of these wee plaster and paint confections you could end up dead.”

This is not a straightforward act of cataloguing as one finds in the water tower photographs of Bernd and Hilla Becher. Further to their already slightly surreal appearance, Pardington introduces subtle methods of distortion through Photoshop, unconsciously suggesting the Alice in Wonderland and trippy, hallucinogenic aspect of fungi. Photoshop adds a layer of indeterminacy to the images, and is merely the newest incarnation of practices that go back to Darwin’s half-cousin Sir Francis Galton (1822-1911), explorer, anthropologist, and pioneering inventor of fingerprinting and, unfortunately, the founder of eugenics. Galton was fascinated by the commonality of some physical traits in ethnic groups, and used composite photography in the 1870s to emphasise and analyse these. Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein closely reproduced these experiments fifty years later in his fascination with the rhizomatic dispersal of traits in family resemblances, though Wittgenstein, as does Pardington in this case, sought a kind of Heisenbergian-like uncertainty, a conceptual ‘fuzziness’ in which all probabilities may co-exist, again suggestive of the reputed psycho-active traits of certain fungi.

The result is these extraordinary images, infused with an aura of something deeply mysterious and magical. Pardington’s dramatic lighting and digital editing and enhancement draws out the sculptural complexity of these fungal forms, focussing in with the kind of intensity one might associate with Albrecht Dürer’s detailed, eagle-eyed studies of divots of grasses and wildflowers, but viewed through a fictive scrim of fantasy. The viewer is left in no doubt that fungi, and through a dim race memory of sympathetic magic, these talismanic models, inhabit a twilight and liminal world.

– Andrew Paul Wood

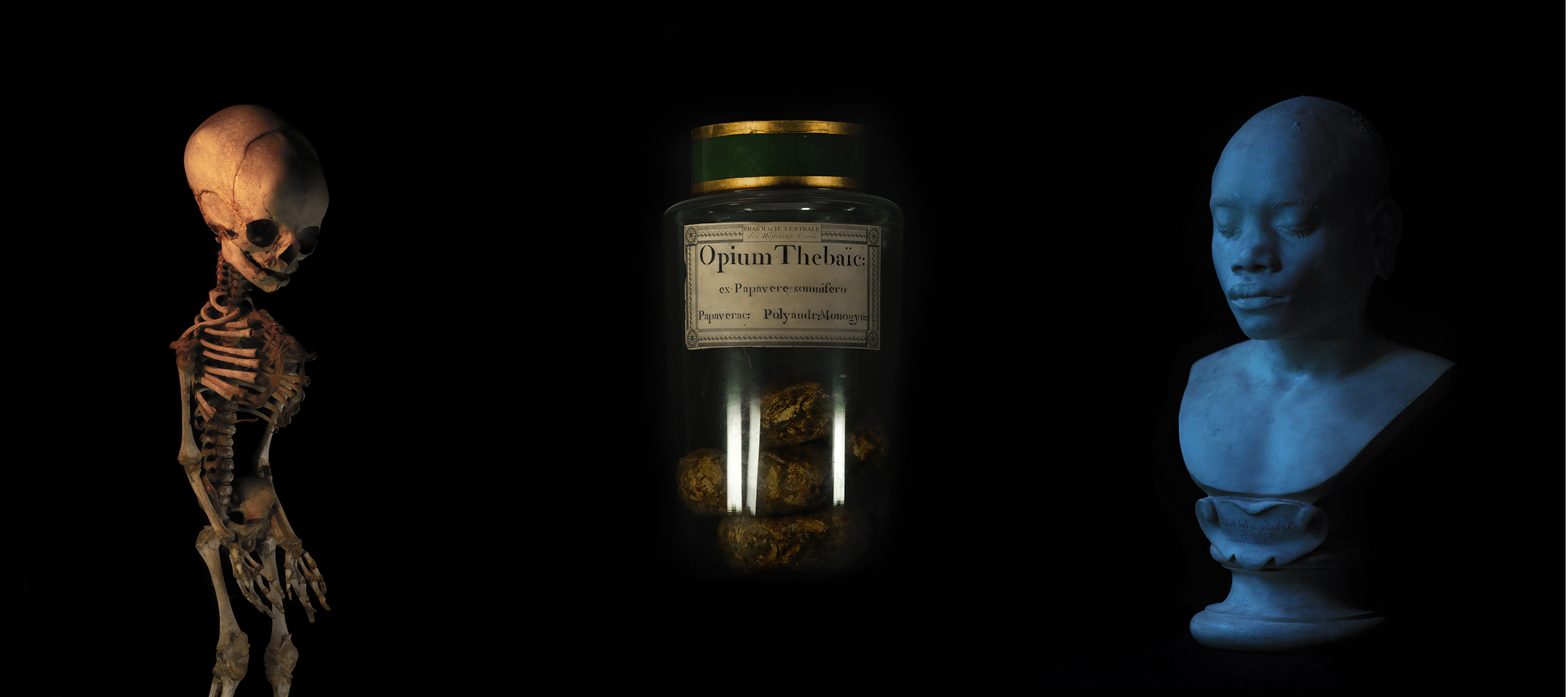

Ex Vivo, 2013–14

Old ocean, there is nothing far-fetched in the idea that you hide within your breast things which will in the future be useful to man. You have already given him the whale. You do not easily allow the greedy eyes of the natural sciences to guess the thousand secrets of your inmost organization. You are modest. Man brags incessantly of trifles. I hail you, old ocean.

— Comte de Lautreamont (Isidore-Lucien Ducasse), Les Chants de Maldoror (1869)

Time in the sea eats its tail, thrives, casts these

Indigestibles, the spars of purposes

That failed far from the surface. None grow rich

In the sea. This curved jawbone did not laugh

But gripped, gripped and is now a cenotaph.

— Ted Hughes, “Relic”

Twice a day the tides that lave and redraft the coastline wash up a diversity of bounty:driftwood, kelp, shells, dead crabs, bones, fishing floats, perhaps a rare paper nautilus,and occasional hints of life in the deep interior depths and cool green hells, or over the blue horizon. After a big storm, more than likely there will be dead seagulls and albatrosses too, studies in greyscale. New Zealand’s long and supine coastline acts like a driftnet, gathering it all up. You never know what gifts Tangaroa will surprise you with, which is part of the magic of it all. If it floats, and falls into the Tasman, the Pacific, the freezing Southern Ocean, or perhaps further afield, hidden currents will probably wash it up on our sand or shingle for a beachcomber to find.

It is beachcombing which provided most of the objets trouvés for this suite of works by Fiona Pardington. Appropriately enough, it starts out as a Pacific phenomenon. The first appearance of the word in print is to be found in Herman Melville’s 1847 novel Omoo which described a community of feckless and outcast Europeans in the Islands who had abandoned Western culture for a life “combing” the beach for anything they could use or trade. Not for the faint of heart, Sappho warns the squeamish against poking the coastal rubble; Μὴ κίνη χέραδασ. While living in Waiheke Island, Fiona regularly explored Rock Bay and Ontetangi beaches, and later Ripiro and Bayley’s Beach, walking her canine menagerie. She, also, was looking for things to use and trade, though these transactions are of an entirely aesthetic sort. She is, as Shakespeare writes of Autolycus in The Winter’s Tale, “a snapper-up of unconsidered trifles”

The albatross feathers allude to the artist’s great love of nature and her Ngāi Tahu, Kati Mamoe and Ngāti Kahungunu ancestry – Māori associations with the deep water, long voyages and return. To Māori, albatrosses, Torora, represented beauty, grace and power, and their feathers and bone were worn by people of rank or adorned the prow of waka taua (war canoes). The (with a nod to Monty Python) ex-gulls. Karoro, the blackbacked gull, were kept as pets by some Māori to control vermin, and were considered an ill omen seen inland. The objects that look like white wax flowers and the plastic casings of fired rifle cartridges. These can be considered symbols of explosive and potentially dangerous energy and transformation.

The philosophy of collecting and salvage moves like an eel up the river from the coast. Like the carnage from the Māori legend of the battle between the sea birds and the land birds, among the fallen, mingling with the gulls and albatrosses are a humdrum sparrow and a young kāhu (hawk). Te kāhu i runga whakaaorangi ana e rā, / Te pērā koia tōku rite, inawa ē! (“The hawk up above moves like clouds in the sky. Let me do the same!”). Here, too, are items that have washed up from the human sea; a crystal ball, a pounamu heart (the heart of Fiona’s whakapapa lies among the iwi of Te Wai Pounamu, the South Island), a hag stone (a stone naturally pierced by water through which those gifted with second sight were, according to legend, supposed to see the future and the other world through, a pewter mug, roses, and a cut glass decanter of water from Lake Wakatipu. Transparent and fragile vessels are important in Fiona’s work, alluding to the tradition of Vanitas painting (remember, you too shall one day die) and often containing water from places significant to the artist. These lustrous objects also reveal Fiona’s virtuosity with light, and photography, after all, is Classical Greek for drawing or writing with light. The eye scavenges.

— Andrew Paul Wood, 2014

Back to Index

Back to Index