Back to Index

Back to Index

FIONA PARDINGTON — Phantasma

|

|

|

|

Phantasma

PHANTASMA: CECI N’EST PAS UN CHAMPIGNON

When I was young I spent childish good times in gumboots out in cow paddocks eeling or collecting mushrooms in buckets. The rain, fog, big bulls or the creeping fingers of mists slipping down from the fragrant native bush never dampened my enthusiasm, as mum’s mushrooms on toast beckoned at the end of each adventure

– Fiona Pardington

And all the time they could, if they liked, go and live at a place with the dim, divine name of St. John’s Wood. I have never been to St. John’s Wood. I dare not. I should be afraid of the innumerable night of fir trees, afraid to come upon a blood-red cup and the beating of the wings of the Eagle. But all these things can be imagined by remaining reverently in the Harrow train.

–G. K. Chesterton, The Napoleon of Notting Hill (1904)

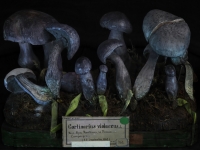

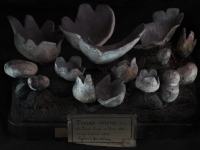

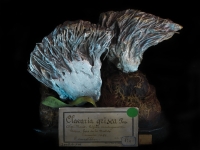

In many ways the Mushrooms: The Champignons Barla series of photographs is simply yet another arrow in Fiona Pardington’s thematic quiver of Eros and Thanatos, the Aristotelian and encyclopaedic collecting policies of the nineteenth century museums, the eighteenth century Wunderkammer cabinet of curiosities, and a pronounced Francophilia. The Musée de l’Histoire Naturelle in Nice, driven by the celebrated naturalist, Antoine Risso (1777-1845), was the first museum to open its doors in that city, in the Place Saint François (the old city square) in 1846. Jean-Baptiste Vérany (1800-1865) compiled its rich collections of birds, molluscs, minerals and fossils, but of interest to us is the private collection of plaster and wax models of fish, flowering plants, and especially fungi of the South of France by Jean-Baptiste Barla (1817-1896). Barla’s collection became part of the museum in 1863 when it moved to its own premises on the site of the current museum, donated to the City of Nice in 1896. It was here on a visit to Nice in April 2011 that Pardington discovered the mycological collection and photographed it for four fungus-filled days.

It is only natural that a culinary culture like the French would be fascinated by fungi. The playwright and satirist Molière named his most famous fictional creation Tartuffe for the old French for truffle, and even named his country estate “Perigord” for the region in France where the black truffle grows. The French invented the cultivation of mushrooms, growing them in the limestone caves at Bourré in the Loirre Valley since the reign of Louis XIV. Every regional cuisine of France uses its own locally growing fungi: truffles, champignon de Paris, channterelle, pleurote (oyster mushrooms), and cèpes (porcini). If you can eat it, the French probably have a sauce that goes with it, and consequently the French know their fungi. The Larousse Gastronomique contains extensive notes on the cooking of mushrooms, and the poisonous ones to avoid. Models like the Barla collection were originally created and circulated around the French municipalities on the typically pragmatic orders of a recently restored Napoleon III so that the public might be educated about which mushrooms were and were not safe to eat.

Among the images of Mushrooms we find a rambunctious cavalcade of names, forms and colours. Each unique specimen is made a character portrait, invested with a personality and supernatural presence as if one had stumbled upon them in some ancient primeval wood. Most of these specimens are poisonous. One of the most deadly fungi of all, though not found among these images, is the Amanita phalloides, the Death Cap or Destroying Angel discovered in 1727 by a French botanist who gave it its Latin name for its phallic appearance rudely jutting erect from the maternal earth. As the common names suggest, A. phalloides is deadly poisonous, and unfortunately resembles some edible mushrooms such as the common Puffball. The fifth century BC Athenian tragedian Euripides lost his wife and three children to a meal of this toadstool. It was used to deliberately poison the Roman Emperor Claudius in AD54 (so that Nero might don the imperial purple) and Pope Clement VII in 1534 to prevent him aligning with France (a few days after commissioning Michelangelo to paint The Last Judgement for the Sistine Chapel), and also caused the accidental death of Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI in 1740.

Mushrooms and toadstools, the fruiting bodies of the fungi family, have long held a peculiar place in human culture and imagination. Some of those which appear in these works are infamous. The white-freckled blood-red cap of the Amanita muscaria or Fly Agaric is notorious for its use by the shamans of many cultures from throughout Eurasia to achieve communion with the divine other realm, though unlike the Psilocybe genus (so called “magic mushrooms” or just plain “shrooms”) they have rarely been sourced for recreational purposes outside of wedding feasts in the Lithuanian hinterland (served in vodka). Among the Turkmenic peoples of Siberia the A. muscaria was first consumed by a shaman and consumed by the rest of the tribe in the much safer form of the Shaman’s urine. A similar practice may have been observed in ancient India, giving rise to the legend of Soma described in the Rig Veda. It has been reported that the Sami sorcerers of Lapland would consume A. muscaria that had seven spots on their caps and claims that it was used by the Parachi-speaking tribes of Afghanistan, and the Ojibwa and Tlicho tribes of North America. It has even been suggested that the Viking Beserkers used A. muscaria to achieve their battle frenzy. The A. muscaria is perhaps the archetypal image of a toadstool (a English children’s argot word, as noted by literary opium addict Thomas de Quincy in his “On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts” (1827), a place where toads were imagined to sit). Arising suddenly from the earth in a season when most other plants are dying, and bearing none of the green of spring foliage, it is easy to see how such an ominous growth would be associated with the magical, the underworld, and the dead – particularly given their frequently poisonous nature.

The abrupt eruption of fungi, particularly in circles, was attributed to shooting stars falling to earth, lightning strikes, mephitic terrestrial vapours, witches, fairies and evil spirits, beliefs persisting in rural parts of Europe well into the nineteenth century. A common folk belief was that dire things would befall any mortal foolhardy to step inside a fairy ring, ranging from being struck lame or blind, or losing one’s way or wits, to being abducted to serve in the realm of Faerie where time moves differently to our world. It was a common rural superstition that cows that grazed in a fairy ring would produce sour milk. The Ivory or Trooping Funnel Clitocybe geotropa is now known as Infundibulicybe geotropa (geotropa deriving from the ancient Greek for “earth turn”). Like misery, it loves company and frequently forms fairy rings – one such being reported in France as a half mile across and estimated at eight centuries old. In ancient Egypt only pharaohs were permitted to eat mushrooms, which they believed were reincarnations of the gods that travelled down from the heavens on bolts of lightning.

This is an association certainly not lost on Pardington:

I loved fairy rings and always made a point of trying to stand inside one on the slim hope of catching a glimpse of a fairy. Being an obedient child, I was informed I should never touch Amanita muscaria, that alarmingly festive creature that that pushed up boldly beneath the arms of dark nested pine trees in a park we lived nearby. Magic was afoot in mushroom season and I was not about to miss it…. I felt close to the earth at these times, endlessly fascinated by its secrets. When I lay on my stomach on the ground and looked closely at the delicate furls underneath the mushroom’s hat, I imagined glancing down to see changelings left by cruel fairies in place of children. The fact I was an avid reader from a very young age meant that I was steeped in fairytales and fairy law, my knowledge extended over Christmas holiday visits to my grandma’s, where I would read her occult Man, Myth and Magic weekly magazines, often scaring myself stiff, at the same time revelling in the power of the unseen, occult worlds and to me mushrooms were the outposts, fairy arena, villages or guard-towers of magical kingdoms and occult territories.

The Flemish painters subtly included toadstools in their depictions of Hell. It is A. muscaria which appears so liberally in picture books of tales collected by the Brothers Grimm, its hyphae baroquely populating the undergrowth of haunted forests full of witches, wolves and menacing anthropomorphic trees. In illustrations from the nineteenth century onward, and in that peculiarly tenacious Victorian genre of fairy painting, they are homes to the little folk, which in more recent times underwent metamorphosis into the more cheerful kitsch incarnation of the Smurf (Les Schtroumpfs in French-speaking countries) village and the giant toadstool (by-product of an extraterrestrial mineral) in Hergé’s L’Étoile mystérieuse (1942), an adventure of boy reporter Tintin later translated as The Shooting Star. One wonders if the Mushroom in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) on which the caterpillar sits smoking who-knows-what in his hookah, was related. Certainly Alice’s dramatic changes in size upon eating pieces of it suggest some kind of hallucination.

The Hydnum auriscalpum is these days known as Auriscalpium vulgare. The original name comes from the Latin auris (ear) and scalpo (“I scratch”) and was bestowed by Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), the “Father” of Latin taxonomy, in 1753 for the fungus’ resemblance to an ear pick. In the model it is posed with a pinecone, it’s usual place of incubation. Also represented here is another of the few fungi named by Linnaeus, Cortinariuss violaceus, the Violet Webcap. The Psathyra corrugis or Red-Edged Brittlestem was once the cause of the accidental poisoning of BBC Wild Food presenter Gordon Hillman, when he was given one instead of an edible variety and then proceeded to drink a beer. Alcohol has a liberating effect on many fungal toxins, and in Hillman’s case resulted in monochrome vision, memory problems and difficulty breathing. Is it any wonder that some societies regard some fungi with awe, as if they might transmit their deadly poison through the air like the evil eye.

The spectacular Clathrus cancellatus is of the foul smelling Stinkhorn family and generally regarded with great superstition and foreboding in Southern France, where it is reputed to grow in cemeteries from the bones of the dead, and cause rashes, convulsions and even cancer. The name Clathrus comes from the ancient Greek for “lattice”, referring to the fungus’ basket-like structure. In the area of the former Yugoslavia its red cousin Clathrus ruber was known as Witch’s Heart. Another Stinkhorn in the collection is Phallus impudicus (imodest phallus, a name bestowed by Linnaeus) which is known for its carrion stench and resemblance to the male anatomy. John Gerard (1545-1611) in his 1597 General Historie of Plants called it the “pricke mushroom” and “fungus virilise penis effigie”, while John Parkinson (1567-1650) in his 1640 Theatrum botanicum called it “Hollander’s workingtoole” – cough cough, nudge nudge, wink wink. Gwen Raverant (1885-1957), the granddaughter of Charles Darwin, remembers roaming the woods of Victorian Cambridge with a Maiden Aunt who would locate the rude fungus by its smell, uproot them, and bear them back to the house and burning them behind the locked door of the drawing room for fear of corrupting the morals of the maids. By contrast, the peasants of Northern Montenegro fed the Stinkhorn to their bulls as an aphrodisiac, and rubbed them on the necks of the bulls to give them strength before bullfights.

The Saffron Milkcap or Red Pine Mushroom Lactarius deliciosus has been eaten for centuries. A fresco in preserved by the ash of Vesuvius in the ruins of the Roman town of Herculaneum depicts this fungus, making it one of the oldest examples of a mushroom known in art. Lactarius viridus (now L. blennius) or Slimy or Beech Milkcap cannot be recommended for the table, though a number of chemicals have been extracted from it which prove to have potentially useful medical applications. The unloved Russula emetica has a slew of names deriving from its emetic and purgative properties: Sickener, Emetic Russula, and Vomiting Russula. It unfortunately resembles edible Russulae and one Sickener mixed in with them will ruin a whole meal. Curiously the British Red Squirrel, little Squirrel Nutkin Sciurus vulgaris, has no such problem with the fungus and has been observed to forage for, store, and eat R. emetic with no ill effects. The Man on Horseback or Yellow Knight, Tricholoma equestre or Tricholoma flavovirens is a tricky customer in that it is widely eaten in Europe, but is in fact poisonous. Named by Linnaeus, the botanical name derives from the ancient Greek for “fringe of hair” and the Latin for “pertaining to horses”. This relates to the fungus’ resemblance to a saddle.

Fungi are so charged with a baggage of meaning and alien looking that they even make their way into Science Fiction. H. G. Wells’ story “The Purple Pileus” (1896) makes a mushroom the muguffin that changes the entire course of a man’s life. Ray Bradbury’s “Boys! Raise Giant Mushrooms in Your Cellar!” (1980) and John Wyndham’s “The Puffball Menace” (1933, essentially a dry run for The Day of the Triffids, 1951) feature enormous weaponised man-eating fungi. Looking at Pardington’s eerie images, one might easily imagine these eldritch organic, biomorphic forms to be intelligent, utterly otherworldly, and quite possibly malign.

Much of the fun in these photographs comes from their false premise. Rene Magritte’s painting The Treachery of Images (La trahison des images, 1928–29, Los Angeles County Museum of Art) depicts a pipe with the inscription “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” – ‘This is not a pipe’. Of course it isn’t a pipe, it’s a painting of a pipe. Likewise Pardington’s images are not fungi, or even photographs of fungi, but photographs of facsimiles of fungi. The images exemplify Jean Baudrillard’s concept of the simulacra as not merely recreations of real things, nor even deceptive recreations of the real; they are not based in the real at all, nor do they hide a reality, they obscure that reality is irrelevant to our existence because we semiotically still recognise these images as fungi. As Pardington notes:

What I love about the Barla polychromed champignons is that these fairy-towers or toad-perches aggravate the incorporeal freedom that the simple materiality of the photograph gestures towards. This freedom imbued in every photographic act positively charges us with its link to the invisible realms of metaphysical thought as equally of any intellectual or scientific ruminations. The photograph always impresses us with its blithe ability to preserve and transmit an intimate physical knowledge of our visible world, although its existence does not necessarily depend on any of the references it springs from. For instance, if I take my photographic portrait, it is not necessarily a correlate of my thought, nor a necessary correlate to my absence, or by any absence of knowledge about any of its situated-ness. Photographs operate anonymously perfectly well, and pouring through the thousands of carte-de-visites at the Vanves fleamarket recently impressed this upon me yet again. When my eyes fall upon the photograph of any of the mushrooms, I imagine Barla’s spade plunging in to the earth, editing out the fairy ring of Russula furcata, activating a kind of transubstantiation where the very this-ness of that day, the haecceity of that day and that hour of September 1862 remains with us thanks to the two styles of time portal that moulage and photography represent to us.

In its own humble way, the mushroom moulage sur vif and its companion photographic portrait can even become an operator in nothing less than ‘a phrasing of history’ (Images in Spite of All: Four Photographs of Auschwitz, Georges Didi-Huberman, University of Chicago Press, 2008, p139), its quiet manifestation shaking down our present grasp on what representation might be…. and what slips in between the cracks in the moulages and settles with a fine aura like fairy-dust is the incommensurable.

Over the years, however, the pigments on the models have changes so that they are no longer scientifically accurate; spectacularly so in the case of the R. emetica. This factor contributes another layer of distance and complexity to what at first glance might be considered a relatively simple body of work. As the artist herself says: “For me it is a very nice undercutting of the scientific drive for arrangement of detailed knowledge and certainty. It adds a further ‘danger’ too, because if you followed the advice of these wee plaster and paint confections you could end up dead.”

This is not a straightforward act of cataloguing as one finds in the water tower photographs of Bernd and Hilla Becher. Further to their already slightly surreal appearance, Pardington introduces subtle methods of distortion through Photoshop, unconsciously suggesting the Alice in Wonderland and trippy, hallucinogenic aspect of fungi. Photoshop adds a layer of indeterminacy to the images, and is merely the newest incarnation of practices that go back to Darwin’s half-cousin Sir Francis Galton (1822-1911), explorer, anthropologist, and pioneering inventor of fingerprinting and, unfortunately, the founder of eugenics. Galton was fascinated by the commonality of some physical traits in ethnic groups, and used composite photography in the 1870s to emphasise and analyse these. Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein closely reproduced these experiments fifty years later in his fascination with the rhizomatic dispersal of traits in family resemblances, though Wittgenstein, as does Pardington in this case, sought a kind of Heisenbergian-like uncertainty, a conceptual ‘fuzziness’ in which all probabilities may co-exist, again suggestive of the reputed psycho-active traits of certain fungi.

The result is these extraordinary images, infused with an aura of something deeply mysterious and magical. Pardington’s dramatic lighting and digital editing and enhancement draws out the sculptural complexity of these fungal forms, focussing in with the kind of intensity one might associate with Albrecht Dürer’s detailed, eagle-eyed studies of divots of grasses and wildflowers, but viewed through a fictive scrim of fantasy. The viewer is left in no doubt that fungi, and through a dim race memory of sympathetic magic, these talismanic models, inhabit a twilight and liminal world.

essay by Andrew Paul Wood